Titanic Tours: Expansion Joints

In the nearly four decades since Titanic’s wreck was discovered at the bottom of the Atlantic, there has been a great deal of focus on the way the ship sank and why things happened the way that they did. A great deal of interest has arisen, naturally, around the ship’s breakup. Given the location of the break, a lot of questions have been asked about the ship’s two expansion joints and whether they could have played a role in her breaking in two as she sank.

As liners grew in size, expansion joints were inserted to help the vessels survive the potentially strong seas they would face. Ships, particularly on the North Atlantic run, experienced some of the most varied and severe sea conditions in the world. Oftentimes, they would encounter series of waves that caught the hull of the ship in between. If the bow and stern were supported by water by the ship wasn’t supported amidships, she could sag there. If the opposite happened, the ship could “hog,” or bend down at the ends. Without expansion joints, the superstructure of the ships, which was built of lighter plating materials and not designed to withstand heavy stresses, would be prone to cracking or could even fail entirely. Even with expansion joints, the larger liners, including Olympic through her long career, could require servicing of these areas after encountering repeated extreme seas.

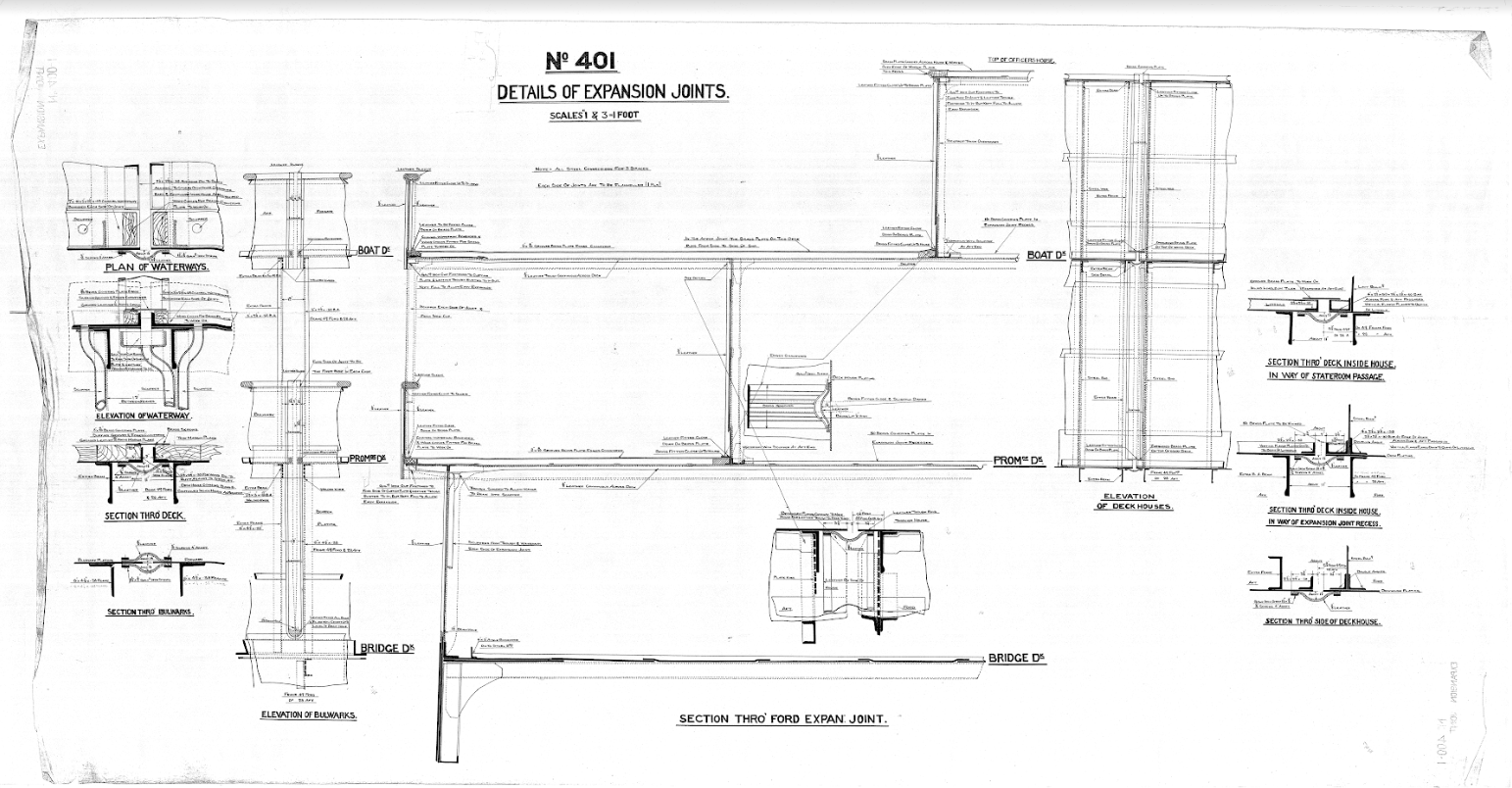

Olympic and Titanic were fitted with two expansion joints, each starting just above the level of B deck and rising throughout the rest of the ship’s superstructure, allowing it to flex slightly in rough seas. The forward of these two expansion joints was located just abaft of the forward funnel at frame 49F. The after expansion joint was located between the third and fourth funnels at frame 28A. This effectively divided her superstructure, the area above B Deck, into three units. Each joint’s horizontal opening was covered with a brass plate. On the top two decks, a leather strip was also included, the leather opening and closing on the bellows principle as the joint opened or closed at sea. These leather strips were also used on the vertical openings in the superstructure. The coverings, of all types, ensured both watertight integrity, with the leather catching and draining away water it collected, and the safety of passengers.

The discovery, in 2006, that Britannic’s expansion joints had a bulb-shaped base (as opposed to the was Olympic’s and Titanic’s joints met at a point), as well as the inclusion of an additional joint amidships, caused many questions to be asked about whether Harland and Wolff felt the joints were a contributing factor in Titanic’s sinking. This can be discounted by the fact that Olympic’s joints were never significantly altered during her more than two decades of service on the Atlantic and also the fact that those joints never failed or were in danger of failing during her long career, including strenuous trooping service in the Great War. The differences in Britannic, from the new shape at the base of the forward joint to the new midships joint, which shifted the after joint to the rear, and even the inclusion of a fourth joint aft where her well deck there was enclosed, can be put down to the fact that the third ship of the trio was significantly different from the first two. With Olympic having experienced some signs of stress in her first year in service (before the loss of her younger sister), it is entirely possibly that Harland and Wolff had already begun rethinking the use of expansion joints before the tragedy.

In any case, the idea that Titanic’s expansion joints somehow contributed to her hull’s failure also founders on the knowledge that these joints only went as far down as B deck and were designed to allow the lighter superstructure to flex. They did not compromise the integrity of her box girder hull design, coming to an end point above the strength deck. It is important to think about what else is located in vicinity of the break, namely the large open space of the reciprocating engine room, and also to acknowledge that Titanic’s design, in modern tests, exceeded the maximum levels of stress that could reasonably be expected. As with so much else with the ship’s loss, a set of circumstances far beyond anything that could have been predicted led to a very tragic outcome.

Next Week: Titanic’s Decks and Deckhouses

Written By: Nick DeWitt

Photo Credit: Titanic Connections Archive