Titanic Tours: Titanic’s Decks

Titanic Tours: Titanic’s Decks Most Titanic enthusiasts and historians dream of the chance to walk the decks of the ship and experience her in all her glory. We imagine ourselves strolling the promenade deck or examining the boats on the boat deck. This week, we’ll explore how those decks were made. A few weeks ago, we looked at Titanic’s frames and how they formed the steel skeleton of the ship, rising vertically to form what we think of as ribs. To these frames and the beams emanating from them, the decks would be attached. It’s important to note that Titanic’s decks were not “flat” by any stretch. They would have had a gentle transverse rise in the center of about three inches. It would have been hardly noticeable to passengers unless they were paying close attention, but it was designed to ensure that water that accumulated due to wave action could easily find it’s way to the sides of the ship and then out the scuppers cut into the hull bulwarks. This rise, called “camber” was present on all of Titanic’s decks. The decks themselves were constructed of steel plates and were assembled along the same lines as the hull, with the in and out system of overlapping edges present. As discussed last week, expansion joints were incorporated into the decks above B deck to allow the rigid steel movement in a seaway. In this way, the decks could flex where needed, but otherwise they were as rigid as the hull itself, while not providing additional strength to the hull girder. The more visible and better-known element of the decks was the wooden sheathing over the steel plates. The wooden planking on her decks was not just decorative, it served a number of important purposes. As steel decks would warm in the sun or chill in the cold, the wood provided a more-uniform temperature for places where passengers and crew would walk regularly. Since wood does not transmit temperature changes, it also helped maintain the temperature inside the ship. Titanic and her sisters incorporated both pitch pine and yellow pine deck planks. The pitch pine was used in high use/high stress areas only, with the yellow pine everywhere else. Planks were typically three inches thick and five inches wide, varying in length to suit the space, and secured to the steel by heavy iron bolts. Once laid, the planks were caulked to help keep them in place. Inside the ship, wood planking was also used in some spaces, but tiles (both linoleum and ceramic), carpet, and parquet could also be found in various spaces. Ceramic tiles were often used in areas where moisture would often be present (lavatories and the swimming pool, for example),while linoleum was found in many passageways, staterooms, and public spaces. Today, tiles from Titanic’s sister Olympic are highly collectible. Next Week: Titanic’s Deckhouses Written By: Nick DeWitt Photo Credit: Titanic Connections Archive Photo Captions: 1: Passengers walk along the boat deck, where pitch pine planks can be clearly seen 2: The well-known (and now highly collectible) two-color tiles found in many parts of the ship are seen here in Olympic’s first class Smoking Room 3: Octagonal tiles are discernable here lining the deck around Olympic’s swimming pool

Design D: The Interior

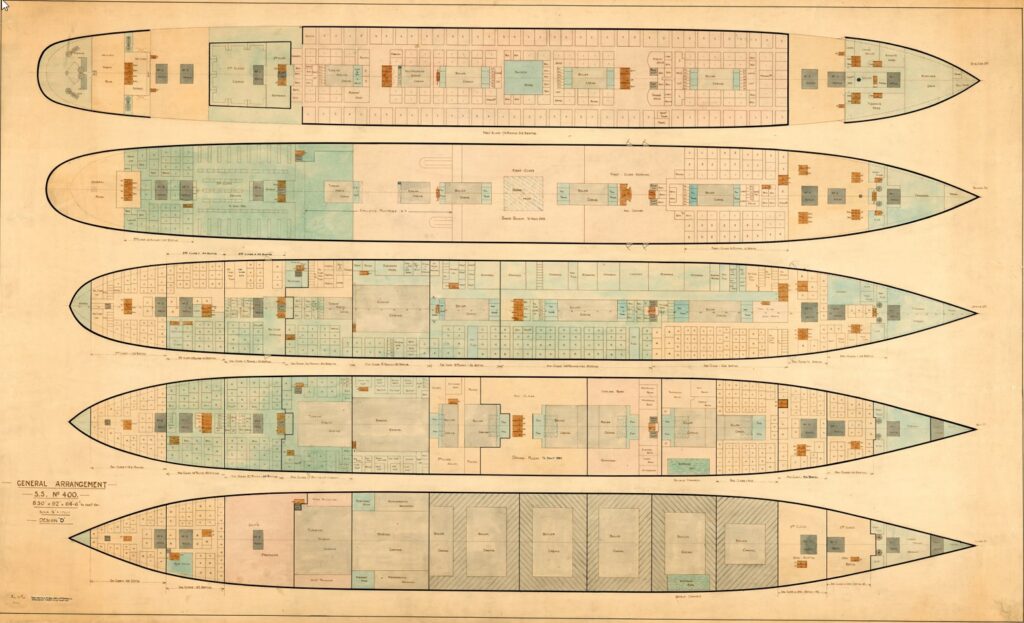

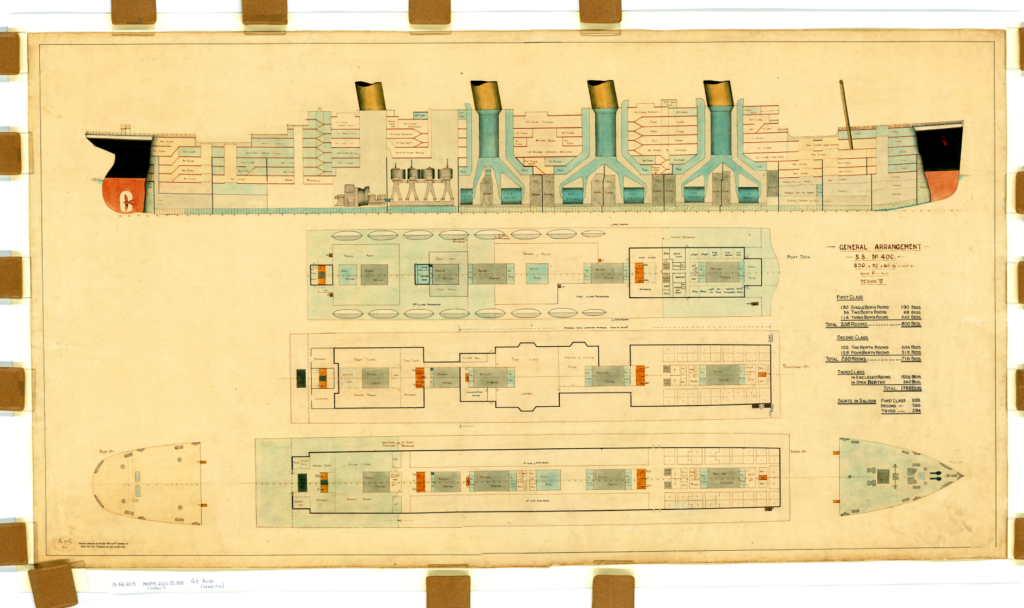

Titanic Design D: The Interior Did You Know… …that the interior arrangements in the original design for the Olympic-class ships, known as Design D, are just as varied from what was actually built as the external features we discussed in last week’s post? While the lack of a second mast after and a clustering of the ship’s lifeboats along the after boat deck is certainly a visual departure from the Olympic-class liners we’ve come to know and love, passengers stepping aboard would have found the ships to be very different from the ones that eventually set sail in 1911 and 1912. The most noticeable change would be the grand staircases. In both cases, these would have been more typical and rectangular staircases, similar to what we eventually saw in the Olympic-class’ second class spaces. The elevators, or lifts, would not have been located behind the forward grant staircase, but across from the front of the staircases, with a port and starboard elevator rather than a stand of three lifts. A deck would be very similar in layout to what was eventually built, with the Lounge, Smoking Room, Palm Court, and Reading and Writing Room all located in the same spots and with the same general shape. The aft part of the deck would have been smaller without the protrusion for the mast and also seems to be lacking the large cargo cranes, although it’s unclear if these are just omitted in the drawings, as no cranes appear around any hatches. B deck is very similar in design to the Olympic, with a large promenade space along the sides, but two major differences jump out from the drawing. The first is the lack of an A La Carte Restaurant for first class passengers. Instead, the second class smoking room is much enlarged. The more interesting change, however, comes near amidships, where there is a large space noted to be for a dome over the first class Dining Saloon. Olympic and her sisters would have a single-deck space for first class to dine, a radical departure from the grand, multi-deck spaces on other large liners built in England, Germany, and France. Design D, at least in this respect, places the Olympic-class ships closer to their contemporaries. This space is also marked on the plans for C deck. In both cases, this unbuilt dome would have taken up space later used for cabins and other small rooms. C deck is otherwise a near-mirror for the as-built ships, with only minor changes to the number and shape of rooms. D deck, however, is radically changed. The first class entrance and a second lounge space, what was later termed the reception room, is much larger in the original plans. Ironically, the final reception room was considered to be a bit too small. The major change here is that the entrances are not walled off from the staircase landing, providing a more open space without altering the rest of the floor plan. Interestingly, the otherwise typical staircase fans out on D deck into a shape more recognizable to our eyes. It is interesting to ponder what Design D’s Dining Saloon would have looked like with a two-deck dome space in its center. The third class General Room is housed here near the stern, as opposed to opposite the Smoking Room for that class on C deck in the final design. E deck holds little more than a few minor alterations, but F deck provides yet another surprise. The Gymnasium, to eventually be found on the starboard side of the Boat Deck, is on the starboard side here instead. The Turkish Bath area is shifted to the port side, where spaces for stewards were eventually located. While this seems a jarring change to us now, this may have been a more practical one in 1912. Olympic and Titanic did not have spaces for changing attached to their Gymnasium. Passengers using the facility would’ve had to pass through public spaces to change, something that would’ve been odd for the times. Most ships that housed a gymnasium at the time had it in the same location as found in Design D. G Deck holds our final major surprises, with the omission of a Squash Court forward being among two notable changes. The other is the location of the ship’s Post Office. Unlike in the final design, where the Post Office was forward on G Deck, Design D places it on the starboard side, but far aft in an area eventually occupied by third class berths. This would certainly have changed some of the story on the night of 14 April 1912, when the mail clerks were among the first to report that their area of the ship was flooding fast. Design D, like most initial designs for any structure, shows a lot of similarities with the what was finally built several years later, but it also shows some interesting differences, some that would’ve advanced beyond typical designs of the time and some which would’ve been a step backward from what eventually became Olympic and Titanic. It is fascinating to look at these designs today and imagine just how different these ships could’ve been. Written By: Nick DeWitt Photo Credit: Titanic Connections Archive Previous Next

Titanic Tours: Making Titanic Watertight

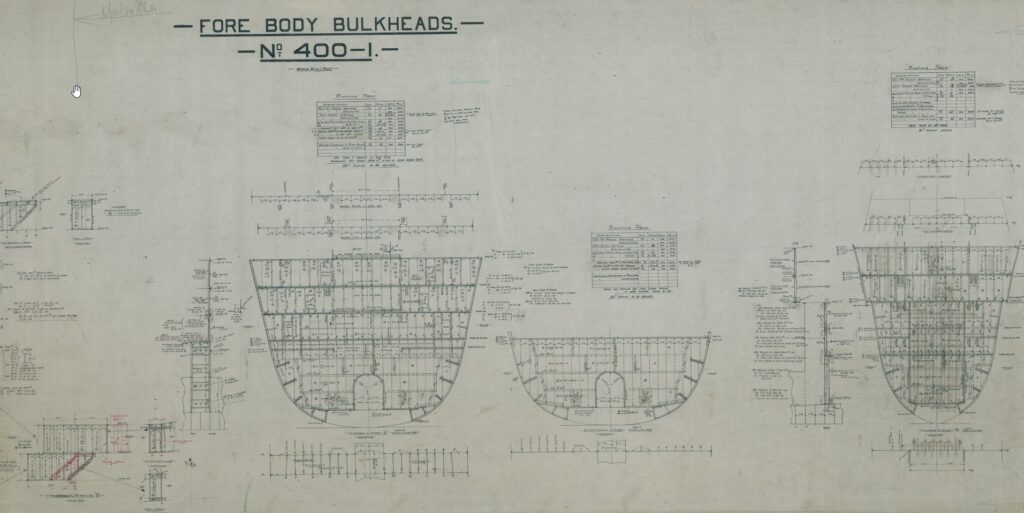

Titanic Tours: Making Titanic Watertight One of the much-ballyhooed features of the Olympic-class liners was their safety features. It would be these safety features, including her watertight doors and subdivision, that would cause the trade publication Shipbuilder, in their 1911 special number, to declare Olympic and Titanic “practically unsinkable.” Surviving a collision at sea was seldom a guarantee, but ships built before Titanic, in some cases many years before, had survived collisions with other ships and even with icebergs. Sinkings, however, were not uncommon in such incidents, with the RMS Republic in 1907 and the RMS Empress of Ireland in 1914 showing that collision damage much less widespread than on Titanic could cause a vessel to founder. Still, despite the accident to Titanic on her maiden voyage, and the later loss of her sister Britannic during World War I, the Olympic-class ships were designed and built with a high degree of safety features. Chief among these features was the cellular double bottom we’ve already discussed in Part 1 of this series. The double bottom formed an inner skin along the vulnerable bottom of the ship. If one of these ships ran over a submerged wreck or rock, it may puncture the outer skin, but would potentially leave the inner skin unscathed, allowing very minimal flooding to occur and permitting the ship to continue with her voyage. Titanic also had watertight bulkheads that divided the lower decks of the ship. Fifteen transverse bulkheads, running from one side to the other, created sixteen watertight compartments. The largest of these would be the space reserved for the ship’s enormous reciprocating engines. Others were of varying sizes, with the bulkheads also not proceeding in a straight vertical line. These bulkheads were lettered from the bow beginning with A and ending with P, omitting the letter I. Each bulkhead rose from the top of the double bottom (known as the Tank Top) as high as either the Upper Deck (E Deck) or the Saloon Deck (D Deck) and remained watertight to that height. The decks themselves were, for the most part, not watertight, lending to the more modern descriptions of the ship’s subdivision as similar to that of an ice cube tray. These bulkheads, pierced by watertight doors that we shall examine in a moment, gave the liners a high degree of survivability in a collision. One of the worst mishaps that could occur at sea was a collision with another vessel that opened two adjoining compartments to the sea. The Olympic-class ships could survive such a scenario. They could also survive an accident that damaged any three of the first five compartments or even the first four compartments from the bow. Unfortunately for Titanic, her damage just exceeded these possibilities, dooming her. A side-swipe collision opening five or six compartments was not a common or likely scenario, so it was believed that these new ships could survive virtually any mishap that would befall them. Most of these bulkheads (excluding E, F, G, H, and J) had watertight access doors built into their structure. When closed, the bulkhead was watertight. At the level of the Tank Top (the floor of the boiler rooms, coal bunkers, and engine spaces), these doors were of the vertical-sliding variety we are familiar with from films and photographs. These doors were more narrow aft of the boiler rooms, the wider doors in the boiler rooms allowing for the transportation of coal from the bunkers in wheelbarrows. The doors were each held open using an electronic clutch that could be released locally or remotely. If released, the doors would drop quickly into the closed position and thus seal the bulkhead. Each door also was equipped with a float system that would automatically close the door if water rose to 1 ½ to two feet above the tank top. Once closed, the only escape from that compartment would be up vertical escape ladders. These variously led to E Deck, where Scotland Road was located, or up to the Boat Deck. Above the boiler and engine spaces on E Deck and D Deck, the bulkheads were pierced by horizontal-sliding watertight doors. These had a similar look and construction, but operated on a rack and pinion system that would press the door firmly against the bulkhead once closed. These doors could be closed locally from either the same deck or from the deck above using hand cranks. Finally, the liners were equipped with several watertight doors on hinges, which operated the same as a standard door, with a rubber gasket around the rim. These could be sealed by pulling the door shut and turning several “dogs” to firmly seal the gasket to the frame. After the sinking, several design changes were made to both the building Britannic and, during her next overhaul, the Olympic. These would expand the two ships’ double skin from the bottom up the sides, extend some of the watertight bulkheads to B Deck, and provide a panel on the ship’s bridge that showed the status of the watertight doors. This panel is erroneously depicted as being aboard Titanic in most films, but it was not a part of her design. Other smaller changes would also be made, and together these would allow the Olympic and Britannic to survive a Titanic-style accident. Each vessel would now be able to float with her first six compartments opened to the sea. Unfortunately, despite these design changes, Britannic would succumb to a mine in 1916 while serving as a hospital ship. Next Week: Titanic’s Expansion Joints Written By: Nick DeWitt Previous Next A look at the bulkhead design from a bow-on perspective, showing the overall shape of the bulkheads and the ways in which various doors pierced them at each deck. Photo: Titanic Connections Archive Previous Next The starboard elevation plan used at the British Titanic Enquiry in the summer of 1912, showing each watertight bulkhead labeled below the hull. Photo: Titanic

Did You Know… All About Titanic’s Design “D”

The Intended Exterior of Design “D” For the Olympic Class Did You Know… …that the original design accepted for the Olympic and Titanic, known as “Design D,” had a number of major differences from the two ships that were eventually launched in Belfast? While there are no known drawings of what presumably would be called Designs A, B, and C, we do have the existing Design D drawings, which are the ones upon which Harland and Wolff would have presented to the White Star Line when the two agreed upon the building of the two ships (with the possibility of a third to be completed later). The presumption has always been that the three “missing” designs would be scaled-up versions of the Big Four liners, particularly Adriatic, the last of that grouping. We can only wonder at what the first conceptions of White Star’s new mammoths might have been. Design D, however, shows not so much a scaled-up Adriatic but a design that is in some ways a radical departure from that of ships of the time and in others very reminiscent of other contemporaneous designs. Perhaps that most noticeable thing about Design D, given how important they would later be to Titanic, are the ship’s lifeboats. The design shows 14 full-size lifeboats with two smaller cutters at the front. This, at least, matches the initial compliment on Olympic and Titanic save for the additional four Engelhardt collapsible boats. All 16 boats, however, are placed aft on the boat deck, with the cutters being just abaft the second funnel and each followed by seven evenly-spaced regulation lifeboats. This would have drastically changed the appearance of the new ships. While the placement of the lifeboats would’ve been different to our eyes, it would’ve followed the practices seen in the Big Four. Adriatic’s boats were situated after just as Design D shows them for the Olympic-class ships. A more radical change in the design, however, would be the omission of a mainmast. While not necessarily the first thing noticed in the drawings, a closer inspection shows only the foremast. This would have completely altered several aspects of the Olympic-class ships and been a complete departure from contemporary designs of the time. The new Lusitania and Mauretania each had two masts, while the Big Four ships each had four. A single mast would not become vogue until near the end of the ocean liner era in the 1950s and 1960s. Beyond the visual changes, the Olympic-class ships would have had to make alternative arrangements for their wireless aerial, which could no longer be suspended between two masts. It is likely that, as with some later vessels such as the Empress of Britain in the 1930s, that this aerial could have been suspended between two of the funnels. As wireless was still in its infancy in 1907 and 1908 when these designs were coming together, this was likely not a primary concern to Harland and Wolff, but if followed through on, it could’ve had an important impact on the Titanic during her ill-fated maiden voyage. The rest of the outward design, as far as we can tell, is likely to be very similar to what we have come to know. Four buff, black-topped funnels, the graceful counter stern, the classic bow shape, and even the overall shape of the superstructure are all there very close to the way we remember them. There’s no complete exterior drawing to show exactly what she would’ve looked like, but it’s safe to say that she would’ve looked similar on the outside. The one other exception is the center anchor and hawse pipe, which do not make an appearance on either the overhead drawing of the forecastle or the starboard elevation. The compass platform might also have been located elsewhere, as a dome over the first class lounge appears to be in that spot in Design D. Internally, however, the ships would be quite different. Next time, we’ll take a look at the internal differences between Design D and the Olympic-class as they were built. The first page of the original drawings for Design D, showing a starboard elevation and overhead looks at the Boat Deck, A Deck, and B Deck (including the forecastle and poop) Previous Next

Wreck Thursday: Decks of a Legend

Wreck Thursday: The Decks of a Legend One of the oft-overlooked, (and taken for granted) details concerning the wreck of Titanic has been the lack of visible ‘Wood’ on the great liners’ upper decks. The Olympic Class Liners had decking that was comprised of several types of wood, the primary of which was Yellow Pine, the others being Pitch Pine, and of course Teak. Much like all ships of the period (and even those today), the Titanic’s decks were comprised of steel that was “sheathed” with wooden planking. The decking was not just for aesthetics… it also allowed for a level, safe, surface to walk on, provide insulation, and served to protect the bare steel from corrosion caused by the salty Atlantic air & water. The Titanic’s foredeck & Aft Poop Deck were sheathed primarily with pitch pine (a bit more durable than Yellow Pine) and the ever-resilient teak wood, which was used as trim around much of the liners deck hardware. Both the Boat deck and promenade deck were sheathed with yellow pine and teak, the latter of which trimmed many of the bulkheads and roofs along the officer’s quarters and even the forward Bridge. Teak was the most resistant to decay, and by proxy, it would almost assuredly never have to be replaced unless the equipment it shielded was ever replaced or removed. All of the wood on Titanic was fastened to the steel deck by way of fasteners and dowels. The planks themselves were several inches thick (and varied in size & thickness) and were finally sealed with caulking. When the Titanic was first filmed in 1985 & 1986 a review of the footage started a hasty rumor that the Titanic’s decks were totally decayed, leaving only their bare outlines on the riveted steel. A review of the available footage came to the conclusion that much of what was seen was, in fact, “Ridges of caulking” as opposed to physical wood planks. Thus the rumor began that the great liner was simply a metal shell, devoid of all form of woodwork. This idea prevailed until the 1987 French IFREMER expedition sent cameras deeper inside Titanic than had been attempted by Dr. Robert Ballard and his camera ‘Jason Junior’ (J.J.). Subsequent explorations conducted to the wreck of Titanic have proven these rumors to be false, and as we shall now see… much of Titanic’s deck still remains to be seen and examined. Lets take a look for ourselves…. Please see images for additional text and information. Post by: Matthew Smathers Information & Images Courtesy Of:Encyclopedia Titanica,Daniel Klistorner,NOAA,Vasilije Ristovic,Father Browne Collection,CyArk Archive,Titanic: The Ship Magnificent,Bruce Beveridge,Ken Marschall,Mark Draper,Riley Gardner,Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute,Rms Titanic Inc.Storied Treasures Collection, Previous Next

Did you know… Titanic’s Reciprocating engines are still upright on the ocean floor?

The Titanic had two triple expansion reciprocating engines. The engines were located in the Reciprocating Engine Room on the Orlop Deck, aft of Boiler Room 1. The reciprocating engines drove the port and starboard propellers. Aft of the reciprocating engines was the turbine engines which drove the central propeller.

Wreck Thursday – First Class Cabin A-11

Wreck Thursday: First Class Cabin A-11 1ST CLASS CABIN A-11 EDITH RUSSEL Titanic SURVIVOR 1st Class cabin A-11 was located on the Starboard side of A-deck almost directly below the ship’s Bridge. Adjacent to the corridor leading to the forward-facing promenade, it was laid out for single occupancy. Though smaller in size than most of Titanic’s 1st Class staterooms, it was comfortably laid out with a brass framed bed, wardrobe closet, vanity with drawers, a couch, privacy screen over the window, and a washbasin. On the Titanic’s ill-fated first, and last voyage, the cabin was occupied by 1st Class passenger Edith Rosenbaum. A Paris fashion reporter, she had expressed disdain for the ‘stuffiness’ aboard Titanic, as well as her uneasiness about traveling aboard, writing to her secretary just one day onboard she ended her letter by saying “How I wish it were over!” Revealed for the first time in 2001 during the filming of ‘GHOSTS OF THE ABYSS” much of A-11 is crushed and buried in debris, however, there are innumerable traces of Miss Rosenbaum’s cabin which remain intact and readily recognizable as we shall now see… *Please See Images for Additional Information* (Check this link out to hear the actual sound of the MAXIX from Miss Russell’s musical pig https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PhwZSPmtHNI) Post by: Matthew Smathers Information & Images Courtesy Of: Encyclopedia Titanic, CyArk Archive, Titanic Archive Project, Titanic: The Ship Magnificent, Bruce Beveridge, James Cameron – Lightstorm Entertainment, Ken Marschall, Henry Aldridge & Son Ltd, Storied Treasures Collection, Harland & Wolff Archive,

Titanic Tours: the Double Bottom

Titanic Tours: the Double Bottom An aerial view of Olympic, looking aft from the bow, showing the subdivision of the double bottom in excellent detail When we discuss Titanic’s watertight subdivision, one of the often-overlooked aspects of her construction is the double bottom. Titanic had what could be called a second or inner skin within the visible exterior hull plates that made up her bottom. As we discussed last week, Titanic had a vertical keel that extended upward from the keel plates themselves. This formed the center point for the double bottom, which took the form of a series of small compartments that formed something of a “honeycomb” at the bottom of the ship under her tank top. Each of these tiny compartments were formed by “floors” at each frame and three longitudinal structures (the keel itself and two margin plates, each located 30’ outboard on either side of the vertical keel). The spaces ranged from 63” to 75” inches in height, being thickest under the heavy reciprocating engines. Each of these “cells” or “tanks” could be utilized for various purposes, from ballast to storage of water. They also were important for Titanic’s stability, preventing water from sloshing around large spaces along the bottom of the ship. Most importantly when it comes to safety features, this cellular bottom and the inner skin it created would help the ship survive grounding collisions where the bottom of the ship was opened to the sea by some obstruction. Rather than a large compartment being opened to the sea and perhaps completely disabling the liner, a small void space would be opened up, giving water much less space to roam free and preventing the ship’s vital components from being damaged or put out of service. As with the keel, Titanic’s double bottom structure can still be viewed today on the two pieces of double bottom that may have formed the final connection between the ship’s bow and stern sections as the liner plunged to the ocean floor. Next Week: Titanic’s Hull Written By: Nick DeWitt Photo Credits: Titanic Connections Archive A view of the Olympic’s double bottom during her scrapping in the mid-1930s from the Titanic Connections Archive

Wreck Thursday – Titanic’s First Class Reception Room

The Titanic’s 1st class reception room was located on D-Deck midships. The first sight for many who boarded the great ship, this opulent room was richly furnished with bright red and ornately designed tile.

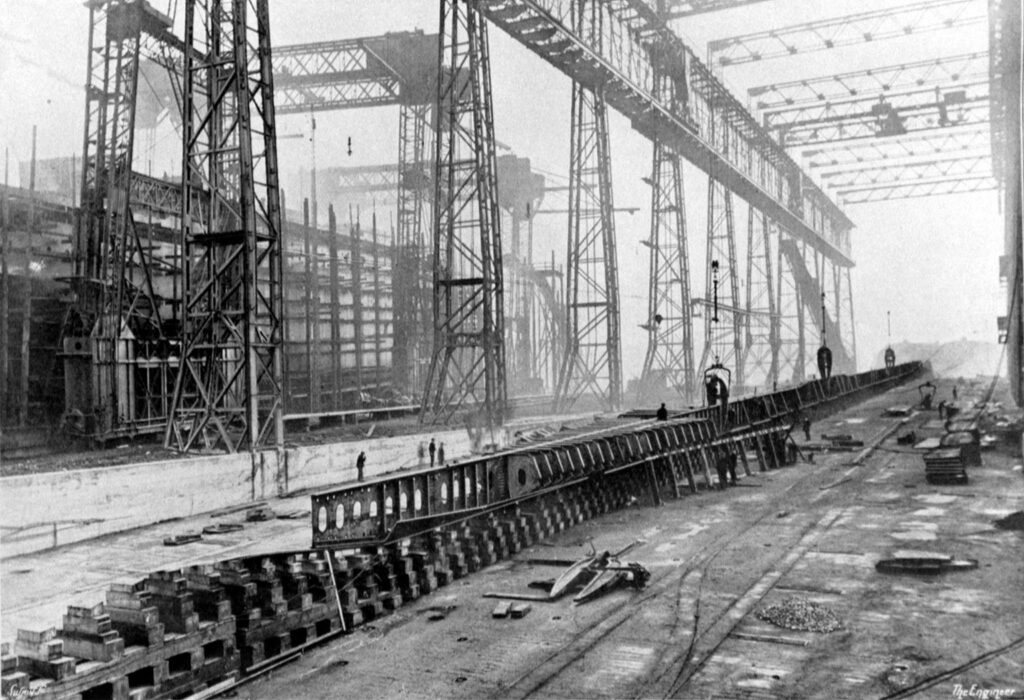

A Titanic Tour: From the Keel Plates up

A Titanic Tour: From the Keel Plates up On 31 March, 1909, the first plates of Titanic’s keel were laid in Slipway No. 3 at Harland & Wolff in Belfast. The keel-laying is the first event in the life of a new ship. Titanic’s keel plates are described in the magisterial “Titanic: The Ship Magnificent” as follows: “Flat-plate design, formed by a single thickness of plating 30/20 inch thick and reducing to 24/20 inch thick toward the ends. The keel plate was 52 inches wide at its broadest point.” A “slab bar” of 19 1/2 inches by 3 inches provided extra strength below this plate. This also, as the authors note, protected the keel plates from damage via grounding and dry-docking. The “vertical keel,” which rose from this line of plate, helped form the central part of the ship’s double bottom and created what is commonly known as the ship’s “backbone.” This spine varied in thickness from 63 inches to 75 inches below Titanic’s gargantuan reciprocating engines. Looking at the ship, the keel is discernible from the rest of the bottom of the hull as a wide strip of riveted plate running down the center line. Initially resting on wooden blocks, like those that can still be seen today in the Thompson Graving Dock in Belfast, the keel would eventually be attached to the “floors,” which formed the outer skin of Titanic’s bottom and the lower plating for her cellular double bottom. Growing first outward and then upward, the hull would eventually radiate out from her keel and form the “box girder” of her hull, an incredibly strong and resilient design that had become common during the 19th century move to iron and steel construction. While Titanic’s keel is not the most glamorous part of her construction, it is one of the most important individual pieces of the ship. Given the immense hogging stresses that the hull was placed under as she sank upright (rather than the more common capsizing that usually is present during a sinking), the strength of her keel determined how long her hull maintained its integrity. With Titanic surpassing even Thomas Andrews’ on-site calculations about the time she could remain afloat, her backbone can be said to have been incredibly resilient. It is ironic that Titanic has been derided in some circles as a “weak” or “poorly constructed” ship. Nothing could be further from the truth. Titanic’s keel was perhaps the last part of the ship to part during her breakup. Two surviving sections of her double bottom were located in the mid-2000s and have since been extensively studied. The keel bar itself can be seen in photos of the sections. Next Week: The Double Bottom Written By: Nick DeWitt Photo Credit: Titanic Connections Archive