Titanic Tours: Making Titanic Watertight

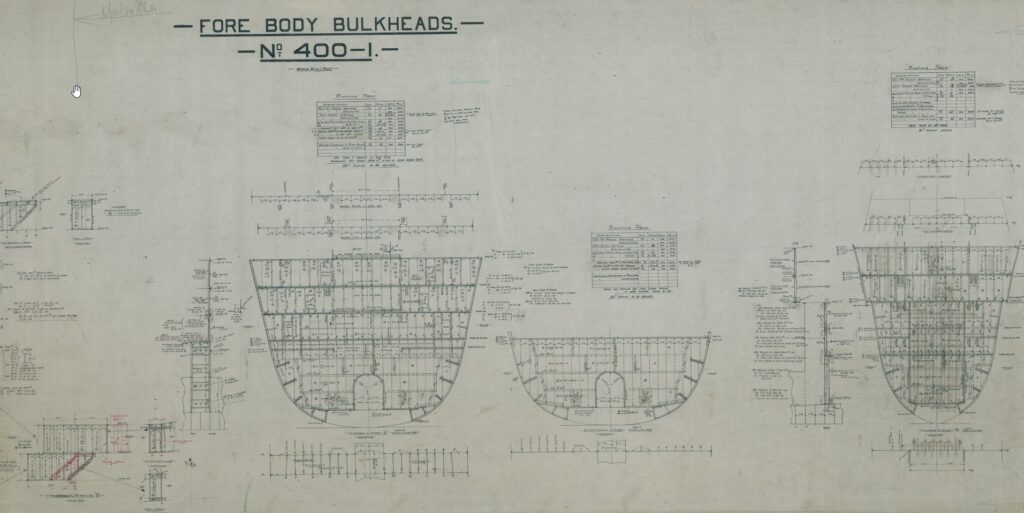

Titanic Tours: Making Titanic Watertight One of the much-ballyhooed features of the Olympic-class liners was their safety features. It would be these safety features, including her watertight doors and subdivision, that would cause the trade publication Shipbuilder, in their 1911 special number, to declare Olympic and Titanic “practically unsinkable.” Surviving a collision at sea was seldom a guarantee, but ships built before Titanic, in some cases many years before, had survived collisions with other ships and even with icebergs. Sinkings, however, were not uncommon in such incidents, with the RMS Republic in 1907 and the RMS Empress of Ireland in 1914 showing that collision damage much less widespread than on Titanic could cause a vessel to founder. Still, despite the accident to Titanic on her maiden voyage, and the later loss of her sister Britannic during World War I, the Olympic-class ships were designed and built with a high degree of safety features. Chief among these features was the cellular double bottom we’ve already discussed in Part 1 of this series. The double bottom formed an inner skin along the vulnerable bottom of the ship. If one of these ships ran over a submerged wreck or rock, it may puncture the outer skin, but would potentially leave the inner skin unscathed, allowing very minimal flooding to occur and permitting the ship to continue with her voyage. Titanic also had watertight bulkheads that divided the lower decks of the ship. Fifteen transverse bulkheads, running from one side to the other, created sixteen watertight compartments. The largest of these would be the space reserved for the ship’s enormous reciprocating engines. Others were of varying sizes, with the bulkheads also not proceeding in a straight vertical line. These bulkheads were lettered from the bow beginning with A and ending with P, omitting the letter I. Each bulkhead rose from the top of the double bottom (known as the Tank Top) as high as either the Upper Deck (E Deck) or the Saloon Deck (D Deck) and remained watertight to that height. The decks themselves were, for the most part, not watertight, lending to the more modern descriptions of the ship’s subdivision as similar to that of an ice cube tray. These bulkheads, pierced by watertight doors that we shall examine in a moment, gave the liners a high degree of survivability in a collision. One of the worst mishaps that could occur at sea was a collision with another vessel that opened two adjoining compartments to the sea. The Olympic-class ships could survive such a scenario. They could also survive an accident that damaged any three of the first five compartments or even the first four compartments from the bow. Unfortunately for Titanic, her damage just exceeded these possibilities, dooming her. A side-swipe collision opening five or six compartments was not a common or likely scenario, so it was believed that these new ships could survive virtually any mishap that would befall them. Most of these bulkheads (excluding E, F, G, H, and J) had watertight access doors built into their structure. When closed, the bulkhead was watertight. At the level of the Tank Top (the floor of the boiler rooms, coal bunkers, and engine spaces), these doors were of the vertical-sliding variety we are familiar with from films and photographs. These doors were more narrow aft of the boiler rooms, the wider doors in the boiler rooms allowing for the transportation of coal from the bunkers in wheelbarrows. The doors were each held open using an electronic clutch that could be released locally or remotely. If released, the doors would drop quickly into the closed position and thus seal the bulkhead. Each door also was equipped with a float system that would automatically close the door if water rose to 1 ½ to two feet above the tank top. Once closed, the only escape from that compartment would be up vertical escape ladders. These variously led to E Deck, where Scotland Road was located, or up to the Boat Deck. Above the boiler and engine spaces on E Deck and D Deck, the bulkheads were pierced by horizontal-sliding watertight doors. These had a similar look and construction, but operated on a rack and pinion system that would press the door firmly against the bulkhead once closed. These doors could be closed locally from either the same deck or from the deck above using hand cranks. Finally, the liners were equipped with several watertight doors on hinges, which operated the same as a standard door, with a rubber gasket around the rim. These could be sealed by pulling the door shut and turning several “dogs” to firmly seal the gasket to the frame. After the sinking, several design changes were made to both the building Britannic and, during her next overhaul, the Olympic. These would expand the two ships’ double skin from the bottom up the sides, extend some of the watertight bulkheads to B Deck, and provide a panel on the ship’s bridge that showed the status of the watertight doors. This panel is erroneously depicted as being aboard Titanic in most films, but it was not a part of her design. Other smaller changes would also be made, and together these would allow the Olympic and Britannic to survive a Titanic-style accident. Each vessel would now be able to float with her first six compartments opened to the sea. Unfortunately, despite these design changes, Britannic would succumb to a mine in 1916 while serving as a hospital ship. Next Week: Titanic’s Expansion Joints Written By: Nick DeWitt Previous Next A look at the bulkhead design from a bow-on perspective, showing the overall shape of the bulkheads and the ways in which various doors pierced them at each deck. Photo: Titanic Connections Archive Previous Next The starboard elevation plan used at the British Titanic Enquiry in the summer of 1912, showing each watertight bulkhead labeled below the hull. Photo: Titanic

A Titanic Tour: From the Keel Plates up

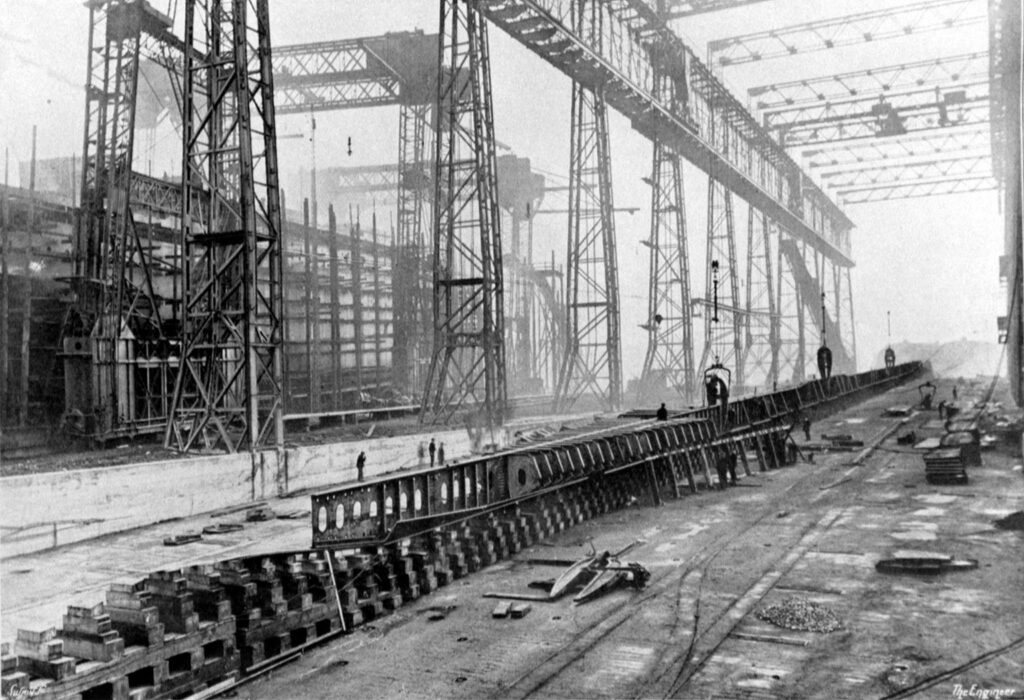

A Titanic Tour: From the Keel Plates up On 31 March, 1909, the first plates of Titanic’s keel were laid in Slipway No. 3 at Harland & Wolff in Belfast. The keel-laying is the first event in the life of a new ship. Titanic’s keel plates are described in the magisterial “Titanic: The Ship Magnificent” as follows: “Flat-plate design, formed by a single thickness of plating 30/20 inch thick and reducing to 24/20 inch thick toward the ends. The keel plate was 52 inches wide at its broadest point.” A “slab bar” of 19 1/2 inches by 3 inches provided extra strength below this plate. This also, as the authors note, protected the keel plates from damage via grounding and dry-docking. The “vertical keel,” which rose from this line of plate, helped form the central part of the ship’s double bottom and created what is commonly known as the ship’s “backbone.” This spine varied in thickness from 63 inches to 75 inches below Titanic’s gargantuan reciprocating engines. Looking at the ship, the keel is discernible from the rest of the bottom of the hull as a wide strip of riveted plate running down the center line. Initially resting on wooden blocks, like those that can still be seen today in the Thompson Graving Dock in Belfast, the keel would eventually be attached to the “floors,” which formed the outer skin of Titanic’s bottom and the lower plating for her cellular double bottom. Growing first outward and then upward, the hull would eventually radiate out from her keel and form the “box girder” of her hull, an incredibly strong and resilient design that had become common during the 19th century move to iron and steel construction. While Titanic’s keel is not the most glamorous part of her construction, it is one of the most important individual pieces of the ship. Given the immense hogging stresses that the hull was placed under as she sank upright (rather than the more common capsizing that usually is present during a sinking), the strength of her keel determined how long her hull maintained its integrity. With Titanic surpassing even Thomas Andrews’ on-site calculations about the time she could remain afloat, her backbone can be said to have been incredibly resilient. It is ironic that Titanic has been derided in some circles as a “weak” or “poorly constructed” ship. Nothing could be further from the truth. Titanic’s keel was perhaps the last part of the ship to part during her breakup. Two surviving sections of her double bottom were located in the mid-2000s and have since been extensively studied. The keel bar itself can be seen in photos of the sections. Next Week: The Double Bottom Written By: Nick DeWitt Photo Credit: Titanic Connections Archive