THE OLYMPIC: OLD RELIABLE

FROM 1911 TO 1913

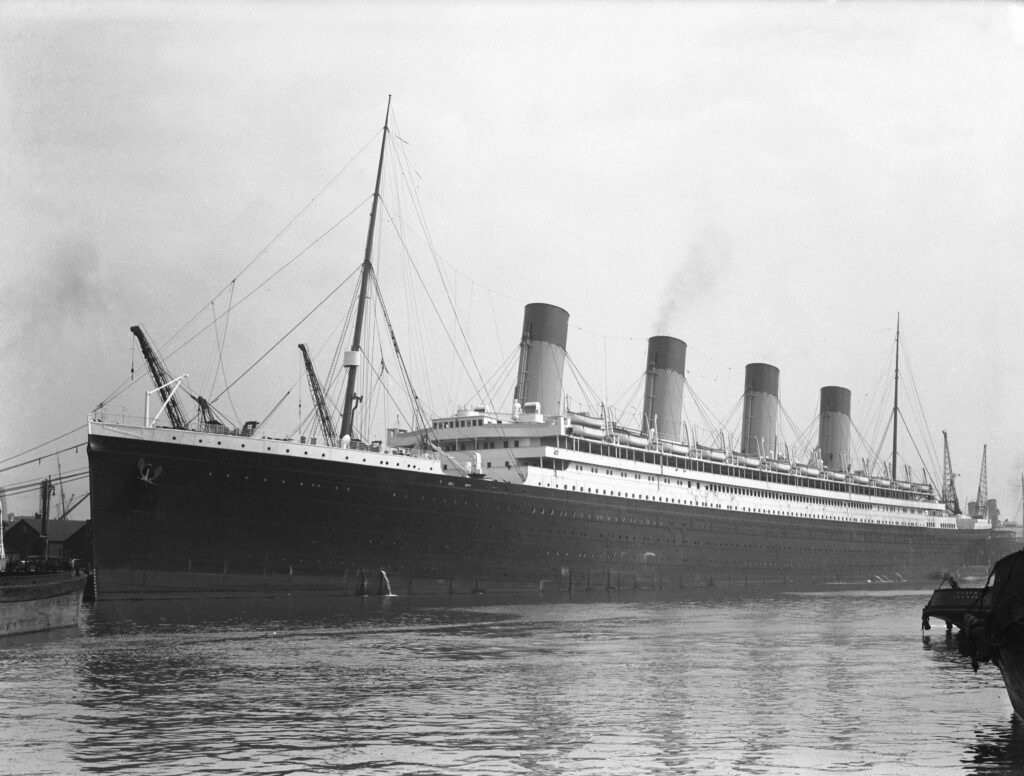

Olympic’s maiden voyage would be every bit the triumph that White Star had hoped for. On 14 June 1911, while her sister and future running mate fitted out in Belfast much as she had, the largest vessel in the world headed for New York for the first time. Fans of Titanic will be familiar with her route: From Southampton to Cherbourg, France, then to Queenstown (now Cobh), Ireland, and then along the Great Circle Route to New York. Olympic would carry just over 1,300 passengers on this first voyage, including J. Bruce Ismay and Thomas Andrews. Her Captain would be Edward J. Smith. All three of these men would be aboard Titanic’s ill-fated crossing less than a year later, with Andrews and Smith among those lost.

Olympic arrived at the Ambrose Light vessel in the wee hours of 21st June, completing her first crossing at an average of just over 21 knots (21.17 to be exact) despite a brief fog delay, showing that she would exceed her design speed once her engines were properly broken in and once she made a voyage not marred by any poor weather conditions. She was feted in New York harbor as she majestically passed up the Hudson to berth at Pier 59, where she would land her passengers for the next 23 years.

Her arrival was not without incident. With everyone, from captain and crew to harbor pilots and tugboat crews still figuring out exactly how to handle a ship so much larger than anything that had come before her, there was a learning curve to master. As she was turning into her berth, she sucked a tug into her side and under her stern, damaging it. It would be her first, but not last, brush with collision. Despite this and some scraped paint on her starboard bow, her maiden voyage was an utter success. Bruce Ismay cabled back the details of the voyage to the line’s Liverpool office, and one can imagine the pride and excitement he must’ve felt as the first of his grand trio was celebrated by all.

Turned around and reloaded with coal and 2,301 passengers, Olympic would depart New York on the afternoon of 28th June to begin her first eastbound crossing, which ended on the 5th of July after a crossing averaging 22.3 knots (eastbound crossings were typically always faster due to sailing with the Gulf Stream). The grand liner was a marvel. While a list of changes to Titanic was compiled to make sure she was even better when she arrived on the scene early in 1912, anyone who had sailed aboard the new Olympic would have been hard-pressed to say anything bad about the experience. Indeed, interested members of both the Cunard Line and the Hamburg-Amerika Line had taken passage in her on her early crossings and found virtually no deficiencies beyond some comments about her being “overly decorated” in some areas.

The new ship’s career would continue without major incident until 20 September 1911, when she would encounter the first truly bad luck of her long career. While passing down the Solent toward the Channel, Olympic was struck on her starboard quarter by the British cruiser HMS Hawke. While the Admiralty would contend that the collision, which sheered the cruiser’s bow off and left a gaping hole in the liner, was entirely the fault of Olympic (this opinion would be upheld by the courts as well), there is evidence that Hawke made incorrect maneuvers, was the victim of a jammed helm, and that Olympic had done all she could to avoid a collision, albeit unsuccessfully. The incident would be dragged out in lawsuits into the wartime period, but more importantly it would send the new liner back to Belfast for repairs, interrupting the construction of her sister.

Olympic returned to sea at the end of November, continuing once again in her steady, popular service on the North Atlantic run. All remained well until the night of 14-15 April 1912. As Olympic sped eastbound, having departed New York the day before, she received an unthinkable wireless message from her sister Titanic, on her maiden voyage westbound since 10 April.

Titanic was sinking, having struck ice. Despite being over 500 miles away, Captain Herbert J. Haddock fired her up all the way, turned her toward her sister’s position, and made all possible speed to the rescue. While she reached nearly 25 knots on this dash in the night, she could not reach the stricken Titanic in time, and she was eventually turned for home the next day, crestfallen. Titanic had gone down with 1,492 souls aboard. 712 survivors had been pulled from lifeboats by the Cunard Line’s Carpathia, but the disaster so unthinkable when the ships were designed had come to pass, leaving the elder sister without a worthy running mate and calling into question her safety.

Olympic would be temporarily equipped with collapsible lifeboats to rest under her regular boats. As every ship on the seas was suddenly scrambling for lifeboats that would accommodate everyone aboard them, boats were in very short supply. Olympic, readying to leave Southampton, experienced a small mutiny when several of her firemen refused to sail in her as she was equipped with what they thought were decrepit boats. It was to be a dark mark in a brief downturn in the liner’s popularity, and she passed the rest of 1912 under a cloud.

In October, she returned to Belfast for the first major refit of her career. She would emerge with a planned 68 lifeboats, up from 20, a double skin to complement her double bottom, and increased height on her watertight bulkheads. She was now not only safe enough to survive an incident identical to that which had put her sister on the bottom of the Atlantic, but she could accommodate every single soul aboard in the event she did encounter something that would sink her. During this time, she received other cosmetic changes to her passenger amenities and cabins, incorporating some of the features that were debuted on Titanic and making permanent some changes that had been roughed together over the previous year.

She returned to the Atlantic run in April of 1913 and was billed heavily as a much safer vessel. Her popularity returned overnight, and she would serve out the next year and then some feathering her nest and awaiting the completion of her sister Britannic, delayed somewhat by new alterations in the wake of Titanic’s sinking.

The plans for her sister’s arrival in service, the possibilities of a Titanic replacement vessel, and her own prosperity, however, were soon to be interrupted by the war that had been brewing for over a decade.

THE OLYMPIC AT WAR

1914 TO 1918

When the First World War began, Olympic was at sea, having left Southampton for New York on 29 July 1914 with 1,140 passengers aboard. Captain Haddock once again swung into action, having her portholes covered and eventually ordering her up to her best possible speed as she neared the American coastline. She reached 25.1 knots during this run, her best speed yet attained, and made it into New York safely and headed for home empty on 9 August. She would continue to make New York runs, berthing in Liverpool when in the UK instead of Southampton to shorten the journey and keep her safer from prowling submarines. By October, however, the plan was to lay her up and await developments.

Her first heroic turn of the war came in October, when she would help rescue the crew of the battleship HMS Audacious, which had struck a mine while on gunnery practice off Ireland. Olympic was on her way home from New York for her final crossing of the year when she diverted in response to the distress call. She used her lifeboats to take off some of the battleship’s crew, and then attempted three times to take the battleship in tow. Each time, however, the tow failed. With the danger of submarines on everyone’s mind, and the conditions aboard the foundering battleship steadily worsening anyway, it was decided to abandon the tow, get the remaining crew off her, and then get the grand liner to safety.

Olympic would arrive in Lough Swilly soon after and be held there along with her passengers and crew for five days before the Admiralty finally released her to complete her journey by landing her passengers at Belfast. The ship and her people had been kept out of sight so that news of the Audacious incident would not get into the papers and risk the morale of the British people early in the war. Only steel magnate Charles Schwab had been permitted off her while she was detained, and only then after he promised Admiral John Jellicoe that he would remain silent about the sinking of the battleship. After her passengers disembarked, the liner was laid up where she’d been born, lying near her incomplete sister Britannic, her construction once again interrupted.

Whereas the Cunard Line’s Lusitania and Mauretania had been built with government subsidies on the condition that they be adaptable to armed merchant cruisers in the event of war, White Star’s behemoths were not built with this in mind. As it turned out, the large liners were ill-suited to such duty anyway, and the two Cunarders would never serve in the role. Lusitania would continue in passenger service until her sinking by a torpedo in May 1915. Mauretania, the current holder of the Blue Riband when the war began, was laid up like Olympic. The large liners had all but disappeared from the world’s oceans by mid-1915, but their absence was to be temporary.

During the summer of 1915, Olympic, Mauretania, and Aquitania were requisitioned as troopships by the Admiralty. While the two Cunarders would also serve at various times as hospital ships, Olympic would be a trooper until the war ended.

She made her first run in September of 1915, carrying troops from England to Mudros for the ill-fated Dardanelles campaign. Now under the command of Bertram Fox Hayes, the man who would command her the longest in her long career, she would continue in this role for some months. Her remaining sister, Britannic, eventually joined her in the England to Greece service, but as a hospital ship. In November of 1916, however, she struck a mine in Kea Channel in the Aegean Sea and sank, leaving Olympic once again without a sister. Having a running mate was, of course, of little concern in wartime, however, and her trooping would continue, her capacity in this role around 6,000.

In 1916, there was a brief period during which Olympic was considered for service ferrying troops to India going around the Cape of Good Hope, but she was not suitable for this service. Her coal consumption on such a long journey would be beyond her bunker capacity.

While she could be retrofitted to carry enough coal, the whole plan made little sense. Had she already burned oil, however, she may have been used in such a capacity. As it was, other work was soon found for her on much more familiar waters.

With the India plan abandoned, Olympic was put once again on the North Atlantic, but not to New York (yet) and not embarking passengers. Instead, she would carry Canadian troops and equipment to the war, berthing in Halifax, Nova Scotia. She become bonded to the people of Halifax and would, years later, make some very well-attended port calls there complete with reunions and remembrances of her gallant war service. She was lucky, as she so often was in her career, however, when she missed the massive explosion in Halifax by a number of days. Had she been in port that December day, it’s nearly certain that she would have been severely, perhaps irreparably, damaged at a time when she was the last of her class and was badly needed for the war effort.

It was during this time that she was painted in dazzle camouflage schemes, which changed some during the rest of the war. She was now armed with six six-inch guns as well, complete with gun crews added to her complement.

Unable to stop to pick up survivors for fear of other subs in the area, the liner continued on to France with only a handful of dented plating and a twist in her stem. Her strong construction had once again stood her in good stead. The American troops aboard presented the ship with a plaque, which remained on display in her forward grand staircase for the rest of her life. Captain Hayes was also awarded the Distinguished Service Order (DSO).

During the war, she would carry around 200,000 troops, more than any other passenger ship in the service, would steam over 180,000 miles, and would become forever known as the “Old Reliable” for her steady service.

The war over in November 1918, Olympic would assume a passenger service of a different kind, carrying American and Canadian troops back home across the ocean. Beloved by all, she returned to Belfast near the end of July 1919 to be refitted and turned back into the grand Atlantic liner she’d been before war had interrupted her intended career.

THE OLYMPIC: OLD RELIABLE

THE ROARING TWENTIES

With peace returning to the world, albeit for only a brief interregnum before another worldwide war would bring more untold death and destruction, Olympic found herself once again in the place of her birth. The luxurious fittings which had been boarded over or removed outright to ready her for trooping service were set to rights. At the same time, White Star took the foresighted opportunity to convert the ship to burn oil instead of coal. She would be the first of the great liners to undergo this conversion, although virtually every other passenger ship of note would soon follow suit. Her post-Titanic refit had been done with this in mind, her double skin being designed to serve as oil bunkerage if the switch ever happened. The move was very economical, saving costs and time, not to mention shrinking her engine room compliment by roughly 300 men.

She would also receive an entirely new setup for her all-important lifeboats, receiving distinctive “nesting” boats that could fit one inside the other on a single set of davits. Her boat deck was now lined with davits, as it had become after the loss of her sister, but the boats were not the mishmash of collapsibles and originals. She would go to sea now with 50 boats in nests of two or three boats each. As Mark Chirnside notes, Olympic likely did not receive the distinctive “gantry” style davits that Britannic had sported because the heavy nature of these would’ve forced her to undergo expensive and time-consuming strengthening of key areas of her superstructure. This arrangement, while providing less open sea vistas on the boat deck, was more cost-effective and, many would argue, much more visually appealing.

Also at this time, the great liner received perhaps one of her more distinctive exterior changes: the gold band that ran around the hull at the base of her white superstructure was shifted down on the hull. This had the effect of making the gold stripe more prominently visible. Whether it was pleasing to the eye or not is a matter of opinion and debate among enthusiasts.

Refreshed, with cleaner-burning (not to mention bunkering) oil now coursing through her boilers, Olympic returned to Southampton in June of 1920 for what amounted to something of a second maiden voyage. She was, in many respects, a new ship after the lengthy and comprehensive overhaul in Belfast. She sailed for New York on 25 June with 2,249 passengers aboard, almost full!

She would resume her previous steady service on the North Atlantic thereafter, becoming one of the most popular ships in the service. While initially without a proper pair of running mates on the express service while the ex-German Bismarck (now Majestic) and Columbus (now Homeric) were completed and readied, she nevertheless carried high numbers of passengers on virtually every crossing, including a number of movie stars like Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford, and Charlie Chaplin.

Not only was Olympic more popular than ever, she was also faster than ever. She was now routinely averaging closer to 23 knots eastbound and around 22 westbound. Rumors of her attaining almost 28 knots in mid-1922 are of dubious credibility, but she was certainly faster as an oil-burner than she’d been with coal. She was also faster than her design speed, although this had been true from the beginning of her life. Her career in this period is dotted with speed-related achievements and several unofficial “races” with other vessels. She seems to have developed a particular rivalry with the American Leviathan, formerly the German Vaterland, which resulted in two stories, each with one of the two ships triumphing. While neither vessel–and no other ship on the waves at the time–could wrest the Blue Riband from Mauretania, Olympic certainly was not turning people off with her non-greyhound speeds.

As the decade moved on, however, a new challenge presented itself to the shipping lines of Europe. For virtually their entire existence up to that point, the big shipping lines had depended on a steady, large diet of steerage passengers who were traveling from the Old World to a new life in the New World. For many decades now, America had held her borders largely wide open, embracing over one million immigrants in some years. The America of the 1920s, however, was less open, more isolationist. World War I had made the United States wary of the global stage, and the days of a thousand or more immigrants traveling in third class quarters on the big liners ended in 1924 when new legislation capped the number of people allowed to enter the United States as immigrants. Eventually, this led to Olympic and her colleagues on the run adopting a new class structure, with third class being recast as “tourist third cabin.” Some of her second class areas were partitioned to provide additional amenities to the new class, and her former third class spaces received a refresh and some upgrades. By the beginning of the 1930s, tourist third cabin would merge with second class entirely and become tourist class.

While Olympic had been an incredibly lucky ship during the war (her postwar drydocking even revealed that, at some point late in the war, she’d survived a torpedo strike to a vital area of her hull when the torpedo failed to detonate), she would once again have a brush with collision in 1924, although this time there was little doubt that she was not at fault. While backing out of her berth at Pier 59 in New York on 22 March, the small liner Fort St George was speeding down the Hudson just ahead of another small liner. Attempting to pass the Olympic as she backed out and turned with the help of tugs, she struck the larger ship in the stern, going under the counter and suffering great damage to her upper works. While there were no fatalities on either vessel, Olympic had suffered a small hole in her stern plating above the waterline and her stern post fractured. While she was able to continue her voyage after a delay to inspect her damage, she would eventually be drydocked and her stern post replaced. As with the incident with HMS Hawke in 1911, legal action dragged on, although this time the White Star liner was vindicated in the end.

Save for this hiccup, Olympic passed the decade in steady and popular service, gradually being modernized during the decade to provide the kind of amenities that passengers were seeking, namely more private bathrooms, something that had been rare at sea when she was conceived nearly two decades earlier. She also received a women’s hair salon to go with her barber shop, two screens for showing movies (one in first and one in second class), tweaks to her dining spaces, and further refreshing to her third class public spaces.

As 1929 moved into its final months, the largest British-built ship on the waves (in tonnage, Aquitania was slightly longer) remained prosperous. Even the great crash and the Great Depression that followed it around the world didn’t immediately spell doom for her passenger totals. As she sailed into the 1930s, however, trouble was brewing on the distant horizon.

THE OLYMPIC: OLD RELIABLE

THE THIRTIES AND THE END OF THE LINE

The beginning of the 1930s, much like the first months of the Great War, were a time of cautious optimism. Just as most believed initially that the war that had begun in August of 1914 would be over before that Christmas, most people initially believed that the crash of the stock market and the resulting depression would be short and world economies would soon rebound.

The Depression, however, was not the only problem for Olympic as she headed toward two decades at sea. While the White Star Line had exited the International Mercantile Marine shipping conglomerate that had once birthed the large ship in January of 1927, it was not for calmer financial waters. A new running mate for Olympic and Majestic, the enormous Oceanic, was ordered in 1928. She would replace Homeric when she was ready, with the smaller and slower ship moving to another part of the line’s vast portfolio of routes. The financial mismanagement and shady dealings of Lord Kylsant, the new owner of the line, would doom this venture, however, and construction was halted a year later and then canceled altogether as the Depression took hold and passenger totals plummeted.

Still, Olympic put up respectable numbers in 1930 and 1931. Later in 1931, she began adding cruises to her normal schedule of crossings, making several trips to “nowhere” for several days. Her most frequent port of call on these was Halifax, where she was still beloved by those who remembered her gallant service during the war. The cruises were successful, but they couldn’t stop the plunging passenger numbers or the financial bleeding. While Olympic was still profitable, changes were coming around her.

In 1932, Homeric left the express service, which would now be handled only by Olympic and Majestic. Always a bit of an odd fit due to her slower speed and smaller size, she would not be replaced by a new ship. Olympic herself made fewer crossings during that year, ending service early to go in for an overhaul that included extensive work to her engine bedplates, reciprocating engines, and other mechanical work. She also received more private bathrooms and, most jarring of all her many updates over the years, much of her oak paneling was painted green with gold details. This included much of her famed grand staircase, then and now to the chagrin of those who found her original fixtures much more beautiful. She would have many cabins receiving coats of paint as well, and in various colors. While this may have made her a more modern-looking ship in an era where art deco was becoming vogue, Olympic had always been popular due to her classic looks inside and out. Reaction to the new look was mixed.

Passenger numbers were bleak in 1933, and all of the large liners of the old guard were feeling the pressure of financial failure. New competition, since the introduction of the French Line’s Ile de France in 1927, was also pressing in. Germany’s Bremen and Europa would hit the scene in 1929 and 1930, respectively, the former finally taking the Blue Riband from the vaunted Mauretania after the Cunarder had held it for 20 years. Italy joined the fray with the Rex and Conte di Savoia in 1932. France was constructing the large, sleek Normandie, which would set sail in 1935. This new tonnage was entering into the old competition. With fewer passengers to go around, every voyage counted, and managers of all lines began to cast doubtful eyes on their older ships.

1934 was another challenging year, although a long-sought rebound began to appear. It was, however, a year of change for Olympic. In July, a merger that had been negotiated for several months came into effect. The old competitors White Star and Cunard became one company, Cunard-White Star Limited. The ships of the line would fly both house flags at the main mast, and the future of all of the older tonnage from both lines was thrown into question. White Star had already sold or scrapped several of their smaller, older ships, and the new company began ruthless contemplation of further scaling down of their combined fleet. With the new Queen Mary’s construction now restarting, it was a near-certainty that many, if not most, of the older express liners would be making their last voyages in the coming years.

Still, there was no reason to believe Olympic would be near the end of her life. Her Board of Trade surveys and the reports of her annual overhauls were always complimentary about her sound construction and, despite heavy use in peace and war, her limited need of repairs and expensive refits.

During the year, Olympic would also suffer her final brush with collision. On 15 May, the liner was nearing New York in heavy fog when she lost contact with the nearby Nantucket Light vessel. Captain John Binks had the ship turned to port, her speed reduced first to 10 knots and then even lower, in order to ensure she avoided the little moored ship. Somehow, however, Binks had put his ship on a collision course, and the tiny vessel was suddenly looming dead ahead out of the fog, unable to move herself. Binks took evasive action, but too late to prevent the accident, and the Olympic hit the light ship in her side. Since she was slowing from an already low speed, she did not cut the ship in half, as the wreck proves, but merely holed her. The damage, however, was mortal, and the light ship soon sank. Olympic immediately launched her emergency boats and looked for survivors. She picked up seven of the ship’s crew of 11, but of these only four survived, including her captain. Olympic made New York after the delay and was once again the subject of extended litigation. This time, as with the HMS Hawke, she would come out the loser, but by the time all the legal action was settled, the great liner was at the breakers.

1935 began with an optimistic tone for Olympic. While it was clear her days as a key cog in the express service were numbered, a number of alternatives and enhancements to her schedule were under consideration in various places. It was clear to everyone that the ship still had useful years left in her. With the international situation once again deteriorating, there were surely memories stirred of her steady service during the Great War, and the possibility that she may be needed again in a new conflict. A series of late-year cruises were announced, meaning her crossing schedule would come to an end earlier in the year than usual. It was also bandied about that she could become a floating hotel in France under new ownership, much as Queen Mary is today in Long Beach, California. Some combination of crossing and cruising was considered as well, and she was certainly one of the ships considered to remain on the express service in some capacity until Queen Mary had a suitable running mate later in the decade.

Mauretania, popular to the last, had preceded her in death, and was moored with her white hull rusting at a Southampton dock. In early April of 1935, Olympic joined her to await her own fate. While she was a candidate to remain on the Southampton to New York run, she was the oldest of the remaining “old” guard of herself, Majestic, Aquitania, and Berengaria. In the end, some combination of factors that may have included her status as a White Star ship in a company that was dominated by Cunard, her age, but certainly not her condition, spelled doom.

Not long after Mauretania made her journey to be broken up unceremoniously at Rosyth, Olympic would make her own funeral march, to Jarrow on the Tyne. She had been sold to Sir John Jarvis, Member of Parliament, with her dismantling to provide work for the hard-hit shipbuilding town. Her fittings were auctioned off not long after her arrival there, ensuring that some of her immense beauty would live on in various places, particularly the White Swan Hotel in Alnwick and Sheffield’s Cutler’s Hall. Her A la Carte Restaurant even went to see once more in the cruise ship Millennium for a time. Even her beautifully-carved Honour and Glory clock was preserved, now being on display in Southampton.

Olympic herself, her fittings stripped away and spread around the world, was slowly dismantled. To the end, she proved a sturdy ship, her scrapping taking longer than expected due to the strength of her construction. In September of 1937, the remains of her hull, now stripped down to no higher than F deck in most places, was towed to Inverkeithing where she could be dry docked and her scrapping completed.

Thus ended the excellent career of RMS Olympic, having completed 257 peacetime round trips with over 430,000 paying passengers aboard, not to mention countless wartime trips carrying around 200,000 soldiers and untold amounts of supplies. Gone, but thanks to her association with Titanic and her own proud, storied history, never forgotten, she remains today one of the grandest of the great liners with one of the most exciting, steady, and fascinating history.