A Titanic Tour: From the Keel Plates up

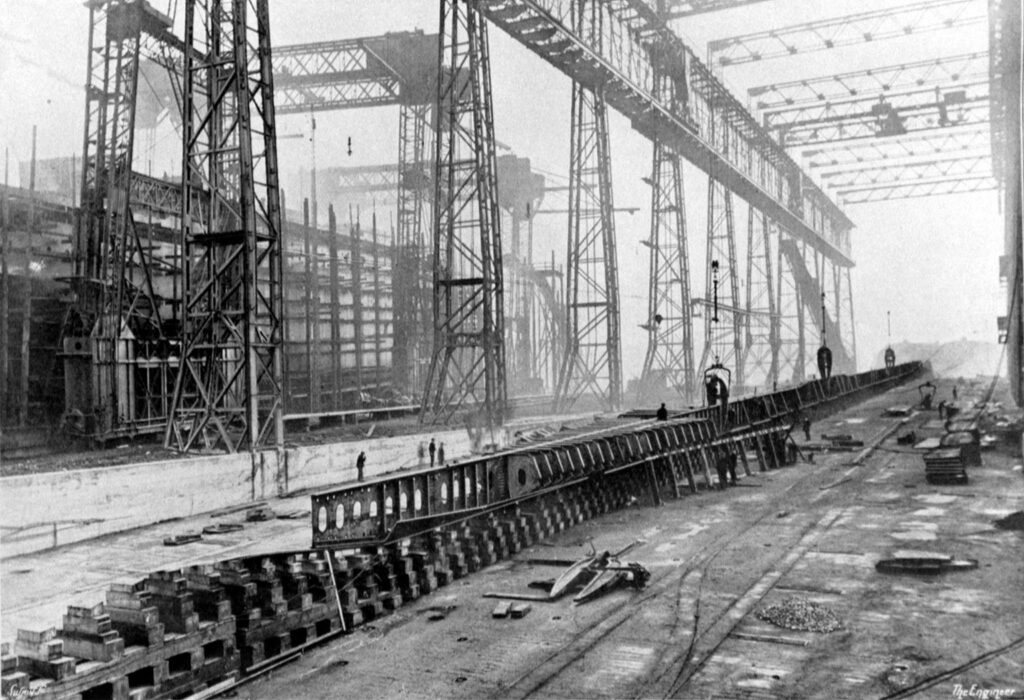

On 31 March, 1909, the first plates of Titanic’s keel were laid in Slipway No. 3 at Harland & Wolff in Belfast.

The keel-laying is the first event in the life of a new ship.

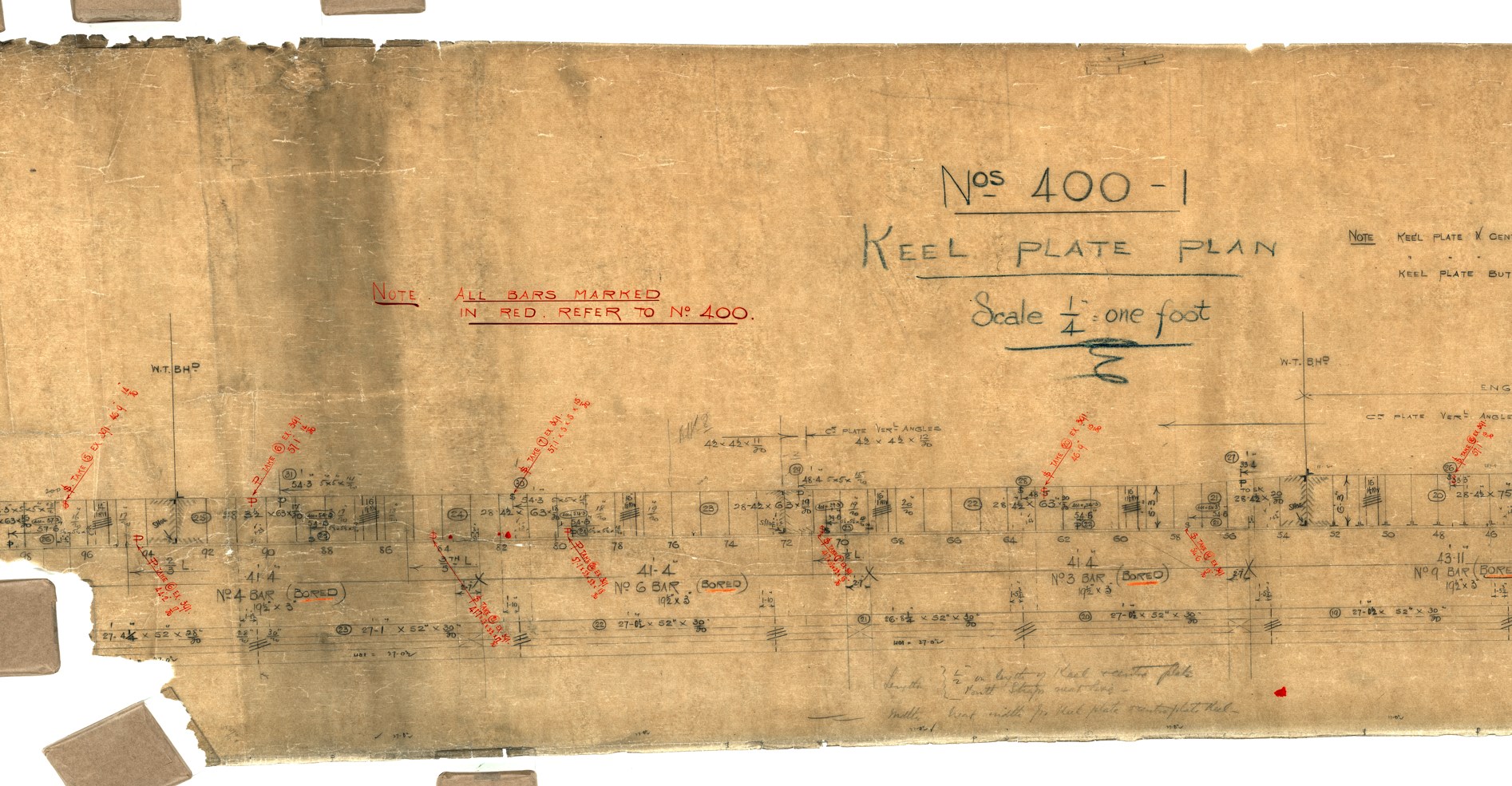

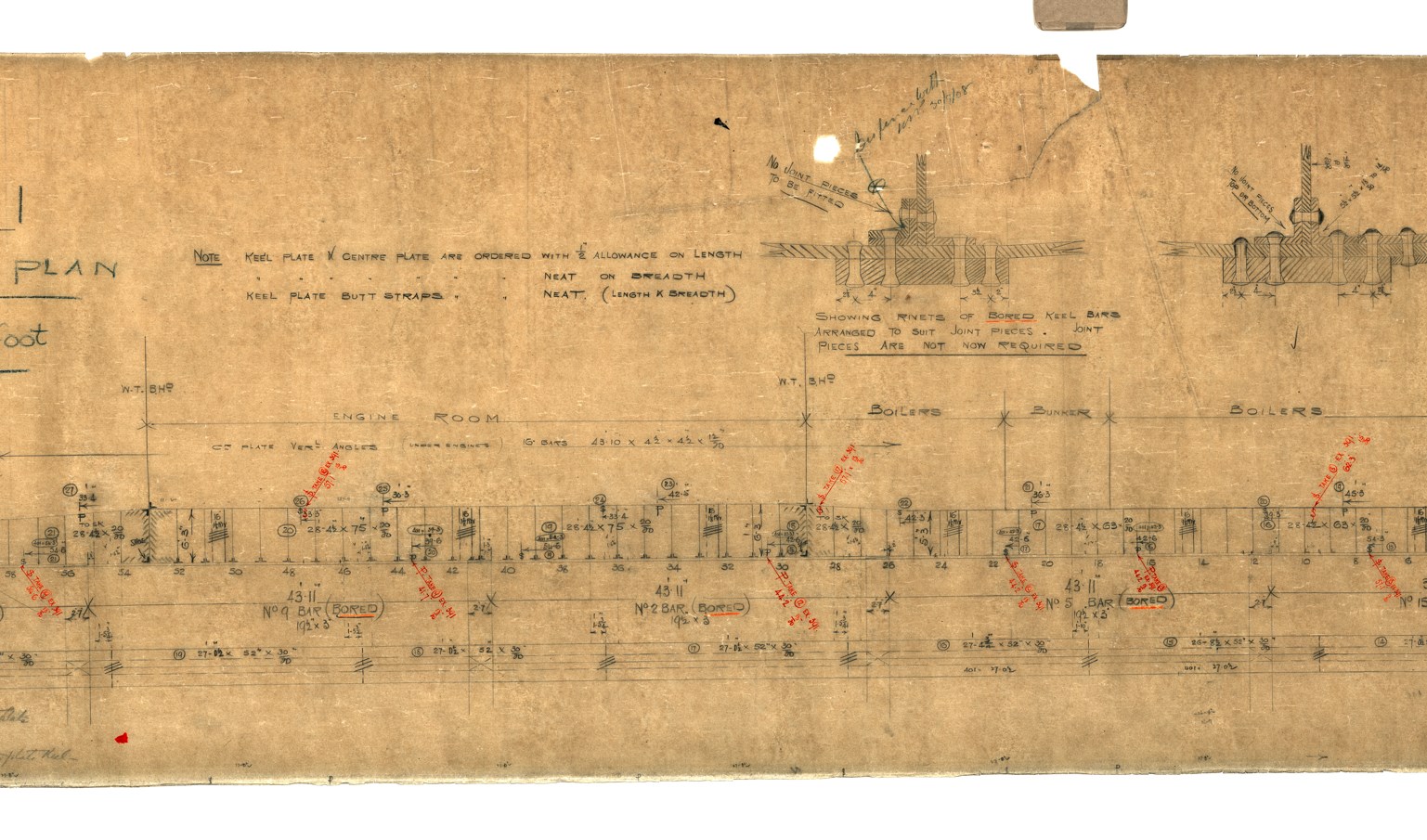

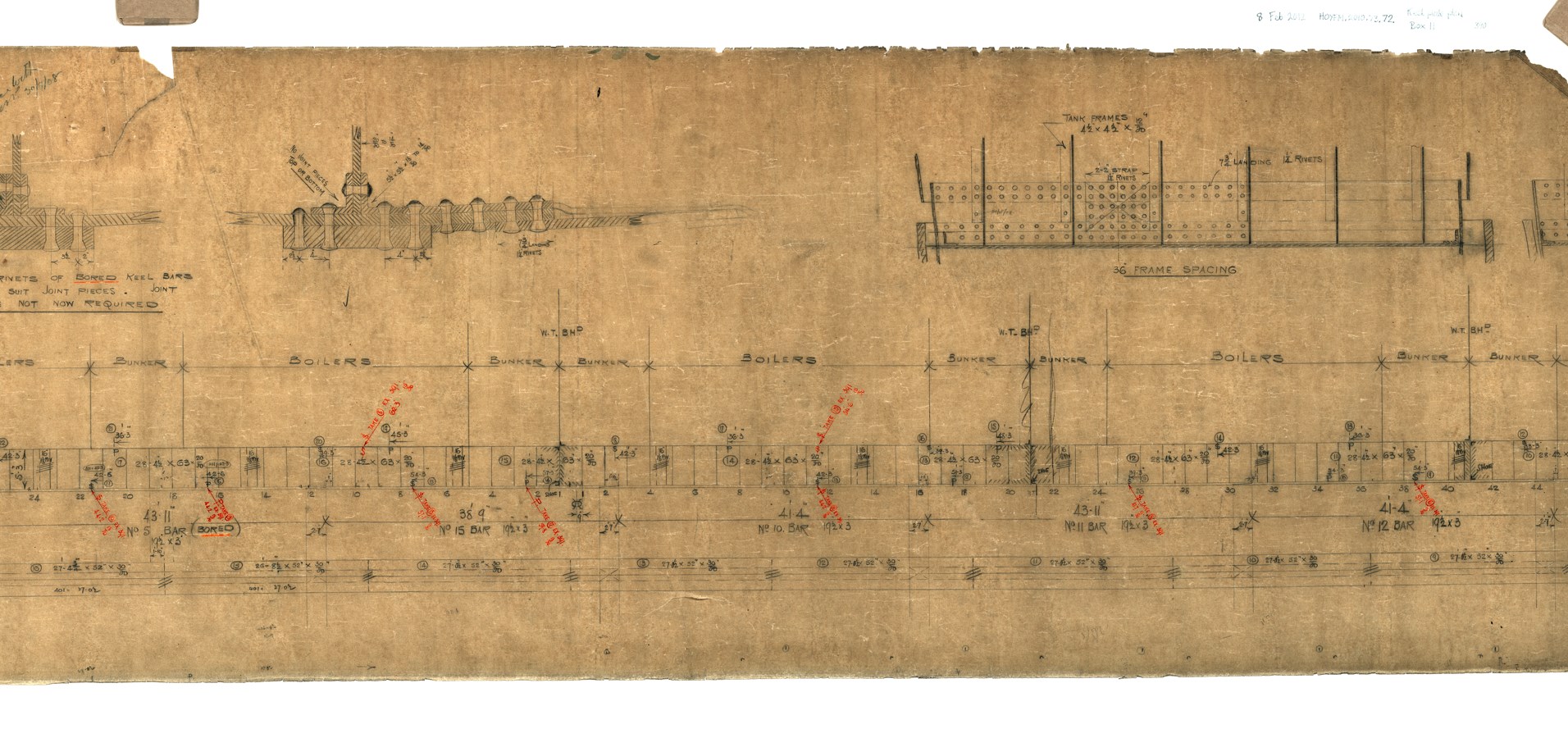

Titanic’s keel plates are described in the magisterial “Titanic: The Ship Magnificent” as follows:

“Flat-plate design, formed by a single thickness of plating 30/20 inch thick and reducing to 24/20 inch thick toward the ends. The keel plate was 52 inches wide at its broadest point.”

A “slab bar” of 19 1/2 inches by 3 inches provided extra strength below this plate. This also, as the authors note, protected the keel plates from damage via grounding and dry-docking. The “vertical keel,” which rose from this line of plate, helped form the central part of the ship’s double bottom and created what is commonly known as the ship’s “backbone.” This spine varied in thickness from 63 inches to 75 inches below Titanic’s gargantuan reciprocating engines.

Looking at the ship, the keel is discernible from the rest of the bottom of the hull as a wide strip of riveted plate running down the center line.

Initially resting on wooden blocks, like those that can still be seen today in the Thompson Graving Dock in Belfast, the keel would eventually be attached to the “floors,” which formed the outer skin of Titanic’s bottom and the lower plating for her cellular double bottom. Growing first outward and then upward, the hull would eventually radiate out from her keel and form the “box girder” of her hull, an incredibly strong and resilient design that had become common during the 19th century move to iron and steel construction.

While Titanic’s keel is not the most glamorous part of her construction, it is one of the most important individual pieces of the ship. Given the immense hogging stresses that the hull was placed under as she sank upright (rather than the more common capsizing that usually is present during a sinking), the strength of her keel determined how long her hull maintained its integrity. With Titanic surpassing even Thomas Andrews’ on-site calculations about the time she could remain afloat, her backbone can be said to have been incredibly resilient. It is ironic that Titanic has been derided in some circles as a “weak” or “poorly constructed” ship. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Titanic’s keel was perhaps the last part of the ship to part during her breakup. Two surviving sections of her double bottom were located in the mid-2000s and have since been extensively studied. The keel bar itself can be seen in photos of the sections.

Next Week: The Double Bottom

Written By: Nick DeWitt

Photo Credit: Titanic Connections Archive