Titanic Tours - The Bridge

A Titanic Connections Feature by Nicholas Dewitt

The brain of any vessel at sea is her bridge. In the case of Titanic, the bridge is where some of the most consequential actions of 14 April 1912 occurred. This week, we’re heading there to take a look at this important space.

Before we begin, a little historical note on the term “bridge.” Sailing vessels did not have a bridge, being instead navigated and commanded from the quarterdeck where the ship’s wheel could be found. But with the arrival of steam power and the equipping of ships with paddle boxes on their sides, the ship’s engineers needed a way to easily get from one paddle box to another and inspect the machinery. This took the form of a raised platform that stretched between the two boxes, forming a literal bridge. When paddles disappeared in favor of the screw propeller, the bridge stayed and became home to the ship’s command and navigating instruments.

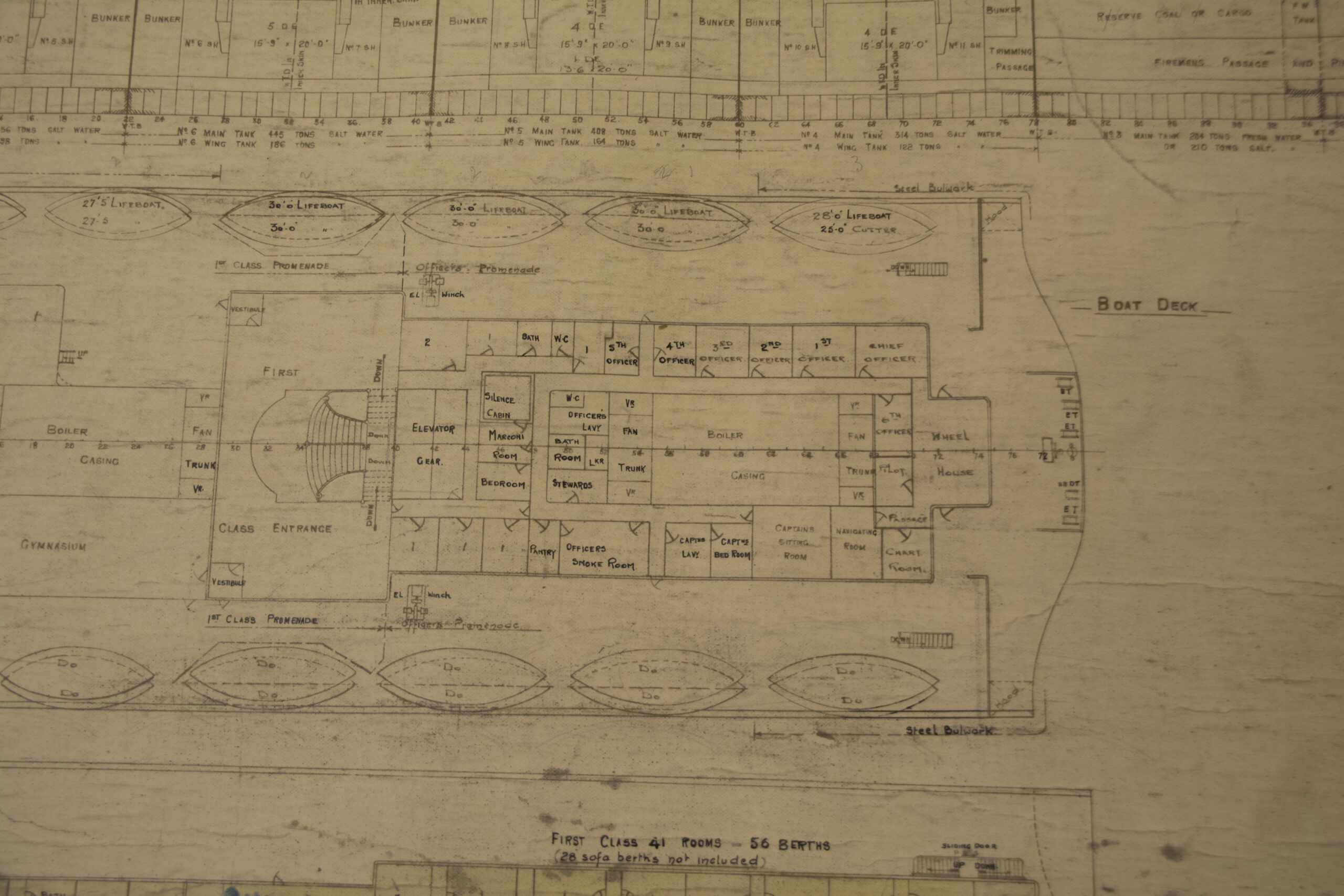

On the Olympic-class liners, as with other liners of the era, the bridge was located forward atop the superstructure. Denoted by a series of nine rectangular windows at the front center of the boat deck, the bridge encompassed a Navigating Bridge just behind the windows, an enclosed Wheelhouse situated behind that space, and encompassed the swept-back wings on either side that ended in a covered “cab” where officers could observe goings on below and to either side. We will explore all of these spaces in today’s tour. Connected to the Wheelhouse were a Chart Room, a Navigating Room, and quarters for a harbor pilot. We will explore these rooms at a later date.

Navigating Bridge

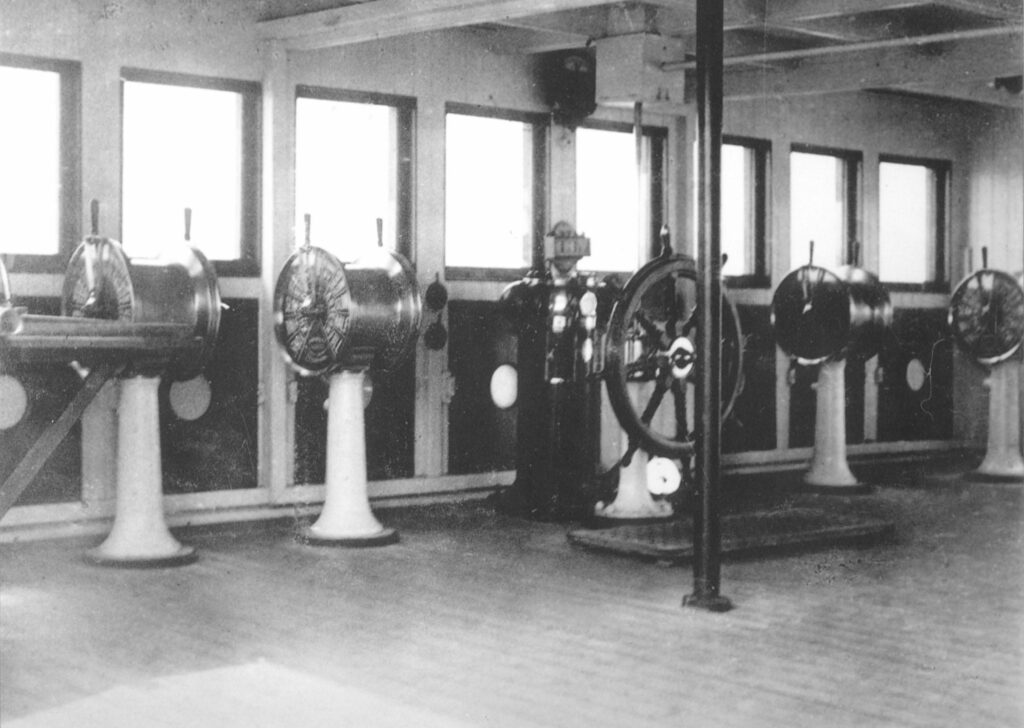

Each space above had a specific function to perform. Let’s begin with the Navigating Bridge. This space contained five order telegraphs, a wheel, and compass binnacle. There were also two small fold-down tables on either side wall that could be used for charts.

While the wheel here was only manned when traveling near shore, the five telegraphs could and would be utilized to communicate with the various engine spaces throughout a voyage. The two outermost telegraphs were connected to the engine room to transmit orders for the speed of the ship. Each of the drums had an indicator for dead slow, slow, half astern, full astern, dead slow, slow, half ahead, full ahead, stop, stand by astern, and stand by ahead. The port handle of these telegraphs would transmit orders for the port engine and the starboard handle would do the same for the starboard engine. These two telegraphs were also connected to one another, so orders need only be “rung down” on one of the telegraphs. A third engine order telegraph was located directly to port of the wheel. This was the emergency telegraph. It had an independent connection to the engine room in case of the failure of the pair of main engine order telegraphs, but was otherwise the same in function. The two remaining telegraphs were for use when the ship was being docked or was near shore. These communicated with the Docking Bridge located on the poop. One was similar to the three engine order telegraphs, but would relay those commands to the Navigating Bridge from the Docking Bridge. The other had a dual set of commands on the side dials, one inner and one outer. Communicating both ways, the Navigating Bridge could send docking commands such as “Let Go Tug” or “Slack Away Stbd.” The Docking Bridge could also indicate information like “All Clear Stbd” or “Not Clear Stbd” to the Navigating Bridge.

At the center of the Navigating Bridge stood the wheel and compass binnacle. The teak binnacle contained a 10” Kelvin-White compass. This was one of four main compasses aboard the Olympic-class ships, with the others being located in the Wheelhouse, a midships Compass Platform, and on the Docking Bridge. The compass inside the binnacle would have been lighted for easy viewing at night.

Behind the compass binnacle was the ship’s wheel, one of three that could be used to steer the ship. This wheel, made of teak and measuring 3’ 9” in diameter, was mounted on a 34” high brass pedestal. This wheel was manned only when the ship was close to shore, but was connected to the telemotor in the Wheelhouse, which then connected it to the steering gear under the poop.

The Navigating Bridge was fronted by nine large windows, with one of the ship’s bells mounted outside and above the center window. Two more windows opened out from the sides of the space, in line with the main engine order telegraphs.

The General Arrangement (GA) plans for the bridge area. These would be similar for both Olympic and Titanic, but Olympic was initially equipped with a curved-front Wheelhouse. Titanic’s was flat-fronted as presented here.

BRIDGE WINGS

Accessed from the open sides of the Navigating Bridge were the two bridge wings, each with a steel bulwark swept back toward an overhanging bridge wing cab with windows on three sides. This area would be used for observation by officers on watch, providing an unobstructed view forward, to either side, and, thanks to the cab extending slightly over the side, downward to the sea.

Immediately outside of the Navigating Bridge, nestled in the space where the bulwark met with the walls of the bridge, a pillar stood for use in mounting a pelorus. Also known as a “dumb compass,” a pelorus was used at times to take bearings. The pillar allowed it to be mounted above the bulwark for this purpose.

Also of use in navigating the ship were the wing cabs, each of which was equipped with the sidelights used in navigation (red to port and green to starboard). These were designed so that they could each be seen from anywhere from dead ahead to two points abaft the beam. Atop each of the wing cabs was a signaling lamp that could be used to communicate with other vessels via Morse. Inside the wing cab, a morsing key could be connected and used in much the same way as the Marconi system was used to send signals over radio waves.

A view of Olympic’s bridge wing and wing cab. Again, the fold-down chart table can be seen in the foreground against the bridge wall. The wing cab clearly shows the large signaling lamp atop it. To the right of the cab near the bottom is the small hatch that would’ve allowed access to the sidelight.

WHEELHOUSE

Directly behind the Navigating Bridge was the Wheelhouse, from where the ship was steered when in open water. It was in this Wheelhouse where Quartermaster Robert Hichens feverishly turned the Titanic’s wheel in response to First Office William Murdoch’s “hard a starboard” order. While the Wheelhouse had five windows at its front, these were often shuttered when the space was in use, forcing the man at the wheel to carry out only the commands received by the deck officers.

The enclosed space was accessed by doors on either side, set just aft of side windows. The front wall of the space was occupied by a flag locker to port and a signal locker to starboard. Here, the flags and other signaling equipment would be kept for ready use when needed.

At the center stood the steering binnacle and telemotor, which connected the ship’s wheel to the steering gear aft. The wheel in the Wheelhouse was slightly smaller than that on the Navigating Bridge, measuring 3’ 6” and was mounted on a 32” pedestal. The telemotor, manufactured by Brown Brothers & Co. of Edinburgh, replaced the direct-drive concept of steering in place on vessels of a much older vintage. This hydraulic system allowed the ship to reset itself to amidships if there were no one acting on the wheel. Today, this telemotor is one of the few remaining recognizable aspects of the ship’s bridge spaces.

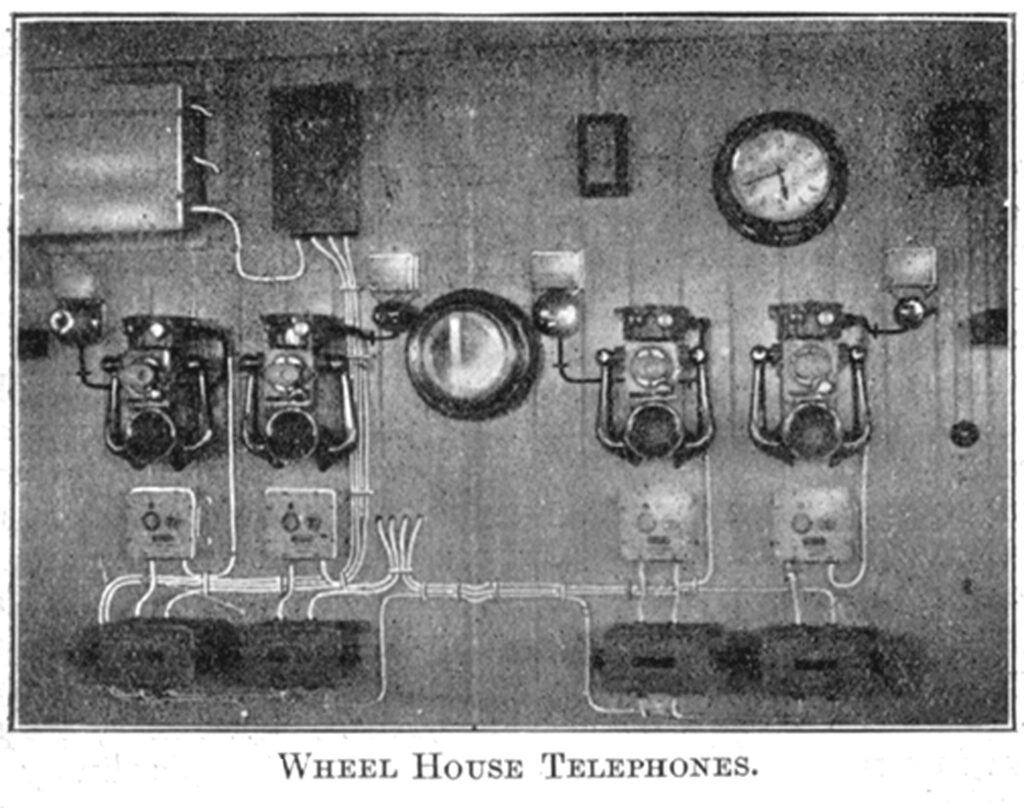

Against the aft bulkhead of the Wheelhouse, various apparatus were located. Among these were telephones that communicated with various parts of the ship. These have become immortalized on film as the place where Sixth Officer James Moody received the call from the Crow’s Nest that ice had been sighted dead ahead.

Other equipment

In various locations around the Navigating Bridge, Wheelhouse, and wings and wing cabs were other pieces of equipment. Various clocks, thermometers, barometers, and a clinometer used to measure the ship’s list were located in spots, as was a locker for supplying the lifeboats. The ship’s whistles could be controlled from various places here as well.

The enclosed space was accessed by doors on either side, set just aft of side windows. The front wall of the space was occupied by a flag locker to port and a signal locker to starboard. Here, the flags and other signaling equipment would be kept for ready use when needed.

At the center stood the steering binnacle and telemotor, which connected the ship’s wheel to the steering gear aft. The wheel in the Wheelhouse was slightly smaller than that on the Navigating Bridge, measuring 3’ 6” and was mounted on a 32” pedestal. The telemotor, manufactured by Brown Brothers & Co. of Edinburgh, replaced the direct-drive concept of steering in place on vessels of a much older vintage. This hydraulic system allowed the ship to reset itself to amidships if there were no one acting on the wheel. Today, this telemotor is one of the few remaining recognizable aspects of the ship’s bridge spaces.

Against the aft bulkhead of the Wheelhouse, various apparatus were located. Among these were telephones that communicated with various parts of the ship. These have become immortalized on film as the place where Sixth Officer James Moody received the call from the Crow’s Nest that ice had been sighted dead ahead.

The telephones on the aft wall of the Olympic’s Wheelhouse, shown along with various other types of equipment used to conn and command the ship.