Titanic Tours - The Funnels

Photographs of a profusion of colorful funnels poking above the piers of New York Harbor are some of the most well-known images of the era of the luxury liner. A ship’s funnels, while an extremely functional necessity in most cases, can also become iconic, immortalized as baubles for passengers to purchase. Today, these are highly sought-after collectibles.

Funnels are not a purely visual element of a ship, however. While the look and number of funnels can sometimes be put down to a stylistic choice, funnels came into existence and have remained a key component of non-nuclear ships for an important reason: to vent the gasses, cinders, and smoke generated by a ship’s engines up and away from the decks and the passengers and crew who roamed them. The history of liners is peppered with examples of ships, such as Norddeutscher Lloyd’s Bremen and Europa, that had their funnels made taller when the too-squat models initially fitted failed to do this basic task well.

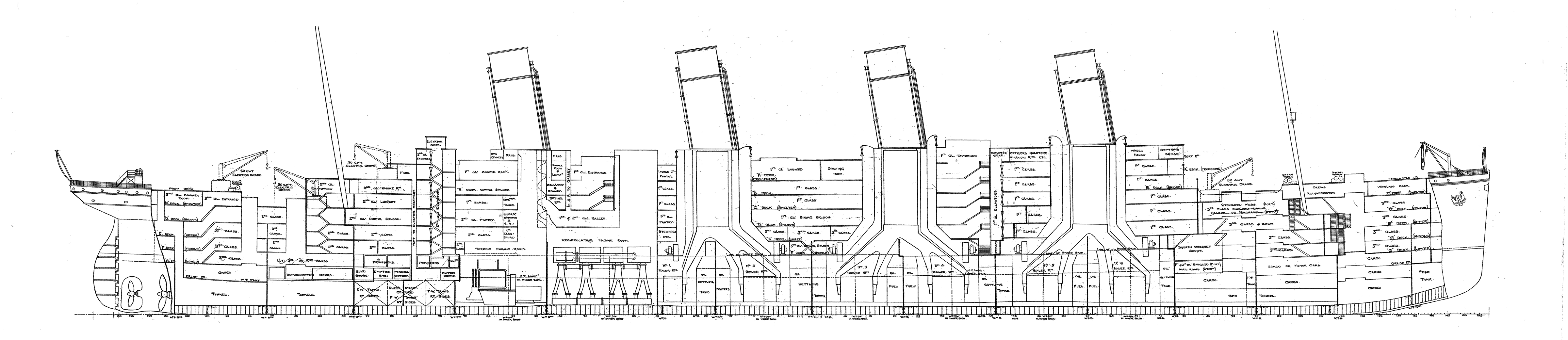

Titanic, as readers probably are aware, had four funnels atop her superstructure. Each of these were oval shaped, measuring 24’ 6” in diameter running fore to aft and 19’ in diameter running port to starboard. While they were level with one another at the top, the uneven height of the deckhouses above the boat deck meant that they rose to various heights, from 70’ for the first funnel to 73’ for the fourth to 74’ for the second and third funnels. The funnels were raked gracefully back, both for style and function, and, unlike the Cunarders Lusitania and Mauretania, spaced evenly and widely along the superstructure. This gave the Olympic-class ships a more yacht-like, graceful appearance than the greyhound racer profiles of the Cunarders.

The funnels were also where the ship’s whistles were located, mounted on the forward side of each funnel. These were reached by a ladder that ran up the front of the funnel. Only the whistles on the first and second funnels were operational, those on the third and fourth funnels being purely decorative to ensure all four funnels looked uniform. Copper steam escape pipes ran up the fronts and backs of each funnel as well. It was from these pipes on the night of 14 April 1912 that steam loudly escaped as the liner came to her final stop, temporarily deafening those on deck.

Funnel colors were important for identifying a ship with her company. As the shipping world expanded, each line developed their own color scheme. The White Star Line had adopted an 18’ tall black band at the top with the rest of the funnel painted in a color known as “White Star Buff.” The exact shade of this color will probably never be known for certain, and is believed to have varied somewhat from painting to painting and throughout the company’s existence. While model makers and artists make their own choice as to how best to represent this color in their creations, the easiest way to describe the color is as a pale orange-yellow. Researcher Robert Read has done an authoritative article on the likely formulations of this color which is linked below for those interested.

The exterior, however, is only a small piece of the story here. The funnels each served various functions for the ship, entailing a varied structure inside each. The exterior tube that can be seen is actually fitted over and connected to an internal tube. This tube was the “working” part of the funnel, designed to conform to the job it was expected to perform.

The first three funnels performed the expected function of funnels everywhere: venting the exhaust gasses and cinders from the ship’s six boiler rooms, with each funnel servicing two of these spaces. Each of these sets of boiler rooms comprised a different amount of fire grate area (the space in which the coal was actually burned to power the ship), so each funnel had a slightly different design. Each boiler’s uptakes stretched toward the center of the ship, where they gradually combined to be vented up through that funnel.

The ship’s fourth funnel has been the source of much confusion over the years. While it is true that only the first three funnels were required for the Olympic-class liners to operate, this fourth iteration did serve in important ways. From a decorative perspective, the fourth funnel conveyed the idea of power and size to a traveling public that had become accustomed to the biggest and fastest ships sporting four funnels. It also allowed for a balanced look, with four funnels spacing evenly along the ship’s profile in a way that would not have been possible with just three.

If it had stopped there, perhaps the fourth funnel could be put down as a true “dummy.” It could be considered as little more than an ornament added for aesthetic reasons only. This funnel, however, had a functional purpose as well. While not required for the ship’s boiler rooms, the fourth funnel provided ventilation for exhaust from the ship’s galley spaces, the extra tariff restaurant on B deck, the first class Smoking Room, the Turbine Engine Room, and various other spaces throughout the ship. While these spaces could possibly have been ventilated through other methods, being able to combine them into a funnel was much more effective.

Each funnel was held in place by 12 stays or shrouds, each measuring 4” in circumference and with six located on each side of the funnel. These were secured at the base of the black-painted part of the funnel at the top and to various pad eyes on the deck at the bottom.

Further Reading: Robert Read’s research on White Star Buff can be found here:

http://www.titanic-cad-plans.com/whitestarbuff.pdf

Content by: Nick Dewitt